I recently acquired a new disc of the movie That Thing You Do! (1996), since my copy had gone missing. The new copy turned out to include an extended edition, with considerable new material (148 minutes, vs. 108 for the theatrical version). The new version lent additional interest to rewatching a favorite story.

Why It Works So Well

I would say That Thing You Do! (“TTYD”) is an archetypal story about a band—it’s the title photo for the TV Tropes topic Music Stories—except it isn’t quite typical, which is one of the movie’s virtues.

I would say That Thing You Do! (“TTYD”) is an archetypal story about a band—it’s the title photo for the TV Tropes topic Music Stories—except it isn’t quite typical, which is one of the movie’s virtues.

TTYD is basically the story of a “one-hit wonder,” a band that has a single major success with a song but never scores again. That theme is lampshaded by the fact that the band itself is (eventually) named the “Wonders.” In the summer of 1964, a college-age rock-and-roll group recruits Guy Patterson to sit in on drums for a college talent show, since their original drummer has broken his arm. The group briefly rehearses their song, an original by guitarist Jimmy Mattingly, the eponymous “That Thing You Do.” When they perform the song at the talent show, the audience loves it. The Wonders proceed to get better gigs; make a recording of the number, which begins to get radio airplay; and are noticed by a promoter, setting them on the road to short-lived stardom.

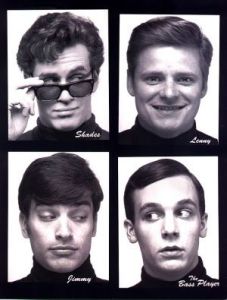

Part of the fun is simply to absorb the ‘60s music culture, which is lovingly re-created—not the high lives of major stars, but the everyday business of performing. Tom Hanks, who eventually takes over as their manager, guides them through the nitty-gritty of publicity gimmicks (he hands Guy a pair of dark glasses to make him distinctive) tours, beach movies, screaming fans, and the like. The amiable cynicism and pragmatism of Hanks’ character grounds the story and makes sure it never spins off into the kind of melodrama all too characteristic of the Music Stories genre.

To me, the most enjoyable part of the movie is where we see a song coming together—a moment I always find exciting. At the talent show, Guy, who hasn’t played in public in a while, is nervous and starts the song faster than they’d played it at rehearsal. Jimmy, miffed at having his creation tampered with, frantically tries to tell him to slow it down. But the faster beat works: kids in the audience start to dance, and the band itself realizes that the song is going over better than in Jimmy’s original mournful, draggy form. While Jimmy is still fuming at the end—“It’s a ballad!”—they can’t deny the livelier version is a rousing success.

To me, the most enjoyable part of the movie is where we see a song coming together—a moment I always find exciting. At the talent show, Guy, who hasn’t played in public in a while, is nervous and starts the song faster than they’d played it at rehearsal. Jimmy, miffed at having his creation tampered with, frantically tries to tell him to slow it down. But the faster beat works: kids in the audience start to dance, and the band itself realizes that the song is going over better than in Jimmy’s original mournful, draggy form. While Jimmy is still fuming at the end—“It’s a ballad!”—they can’t deny the livelier version is a rousing success.

I always love seeing something like this: a musical piece when it finally gells, when the fusion of the musicians’ talents works to make the underlying soul of the song shine through. Music and Lyrics (2007), for example, works the same kind of magic, though spread out over a longer period than a single performance. It’s rare when we get a chance to see the creative process actually at work, right there in front of us. It’s one thing to see the final end product performed, but to be in on the formation of what becomes a first-rate work is both inspiring and exciting—even when it’s half-accidental and serendipitous, as here; or maybe because that spark jumps forth unpredictably.

I always love seeing something like this: a musical piece when it finally gells, when the fusion of the musicians’ talents works to make the underlying soul of the song shine through. Music and Lyrics (2007), for example, works the same kind of magic, though spread out over a longer period than a single performance. It’s rare when we get a chance to see the creative process actually at work, right there in front of us. It’s one thing to see the final end product performed, but to be in on the formation of what becomes a first-rate work is both inspiring and exciting—even when it’s half-accidental and serendipitous, as here; or maybe because that spark jumps forth unpredictably.

This sense of creative vitality is reinforced by the general high spirits of the characters—that effervescent sense of something new and wonderful. When their song first gets played on the local radio station, the band members and Faye, Jimmy’s girlfriend, go madly dashing around the town, alerting each other that they’re on the air, dancing around the appliance store where Guy works and turning up the radio full blast. While the effervescence wanes over the course of the story as the business of music becomes more mundane, we never quite forget that boundless enthusiasm with which the group started out.

This sense of creative vitality is reinforced by the general high spirits of the characters—that effervescent sense of something new and wonderful. When their song first gets played on the local radio station, the band members and Faye, Jimmy’s girlfriend, go madly dashing around the town, alerting each other that they’re on the air, dancing around the appliance store where Guy works and turning up the radio full blast. While the effervescence wanes over the course of the story as the business of music becomes more mundane, we never quite forget that boundless enthusiasm with which the group started out.

Not Your Average Music Story

The typical movie about a band or other performing group tends to follow the same pattern as a certain type of sports story. (That is, for imaginary bands: biopics about real groups don’t necessarily track that pattern, bring constrained by history.) A group of young underdogs gets together, challenges the stuck-up ruling clique, engages in something like a “battle of the bands,” and emerges with a satisfying victory.

Different shows may ring different changes on that model, but there tends to be some competitive moment that brings the story to a well-defined climax. Take, for example, Pitch Perfect 1 and 2 (2012 and 2015—I haven’t seen the third installment), featuring a motley a cappella group. School of Rock (2003), with Jack Black and a mob of precocious grade-schoolers, ends with a Battle of the Bands competition. The obscure but surprisingly good Bandslam (2009) is named for a band competition the scrappy underdogs are determined to win. (In that film we also get a sense of a song coming together for the first time, at about 1:10.) If we move to dance rather than singing, there’s the competition at the end of Shall We Dance (2004). A cheerleading competition caps off Bring It On (2000). Et cetera . . .

Different shows may ring different changes on that model, but there tends to be some competitive moment that brings the story to a well-defined climax. Take, for example, Pitch Perfect 1 and 2 (2012 and 2015—I haven’t seen the third installment), featuring a motley a cappella group. School of Rock (2003), with Jack Black and a mob of precocious grade-schoolers, ends with a Battle of the Bands competition. The obscure but surprisingly good Bandslam (2009) is named for a band competition the scrappy underdogs are determined to win. (In that film we also get a sense of a song coming together for the first time, at about 1:10.) If we move to dance rather than singing, there’s the competition at the end of Shall We Dance (2004). A cheerleading competition caps off Bring It On (2000). Et cetera . . .

But TTYD is not that kind of story. The only real competition involved is the talent show at the very beginning. Rather than moving to a victorious climax, TTYD traces the whole arc of a one-hit wonder band, from humble origins, to a degree of national celebrity, to disintegration under the pull of the band members’ conflicting interests. At the end of TTYD, the Wonders actually break up, with one joining the military, another running off for a Vegas marriage, Jimmy quitting in a huff due to “creative differences,” and the band in breach of contract (though Tom Hanks’ character placidly informs Guy that “nobody’s going to jail”). A band that ends in a breakup doesn’t exactly follow the trope.

Yet the story isn’t a downer either. There are some strong secondary plotlines running through the movie. One is Guy’s devotion to jazz music (an infallible sign of artistic integrity for a character in a film). During the Wonders’ peak period of success, he gets a chance to meet, and then jam with, his idol, jazz pianist Del Paxton. It’s clear that Guy, at least, is going to have the chance to pursue his dreams. Indeed, the American Graffiti-style epilogue tells us that each of the four original band members went on to a reasonably satisfactory career (though not necessarily in music).

Moreover, there’s a well-drawn romance that also runs throughout. Faye is supposedly Jimmy’s girlfriend, but he’s too wrapped up in his musical ambitions to pay any real attention to her. Meanwhile, Guy, whose former girl has dumped him for a handsome dentist, is the one who looks out for Faye, makes sure she’s included in the group’s travels, and takes care of her when she’s ill. It’s positively endearing when they finally get together at the end—and the epilogue describes them as founding a music conservatory together. The successful resolutions of these ancillary plots offsets the somewhat tragic arc of the main storyline and leaves us feeling good about the characters’ fates, despite the meteoric rise and fall of the group.

Moreover, there’s a well-drawn romance that also runs throughout. Faye is supposedly Jimmy’s girlfriend, but he’s too wrapped up in his musical ambitions to pay any real attention to her. Meanwhile, Guy, whose former girl has dumped him for a handsome dentist, is the one who looks out for Faye, makes sure she’s included in the group’s travels, and takes care of her when she’s ill. It’s positively endearing when they finally get together at the end—and the epilogue describes them as founding a music conservatory together. The successful resolutions of these ancillary plots offsets the somewhat tragic arc of the main storyline and leaves us feeling good about the characters’ fates, despite the meteoric rise and fall of the group.

The Music

The songs we hear were written specifically for the movie—but you’d never know it. The songwriters, who include Tom Hanks, Adam Schlesinger, Rick Elias, Scott Rogness, Mike Piccirillo, Gary Goetzman and Howard Shore, pull off an amazing simulation of early 1960 styles. Even aside from the title piece, they give us dead-on compositions in the style of the Ray Conniff-type pop chorale (“Lovin’ You Lots and Lots”), the solo chanteuse (“My World is Over”), the girl group (“Hold My Hand, Hold My Heart”), the pseudo-Beatles crowd-pleaser (“Little Wild One”), and more. To my mind, a successful imitation or pastiche of someone else’s style is a noteworthy artistic achievement; the music here lends an authentic-sounding ’60s air to the film.

The title song is an even more remarkable accomplishment. In the first place, it sounds exactly right to have been a hit around 1964. In the second place, it’s so good (IMHO) that it holds up even through the dozen or so times we necessarily hear it, in whole or in part, during the movie. “That Thing You Do” is still on my playlists; it’s irresistibly catchy.

How did Hanks and company pull that off? For one thing, while the instrumentation and overall sound puts it squarely in the ’60s, the song is not the four-chord masterpiece one might expect. The chord progressions are more sophisticated than those of the average rock-and-roll song of the period. Even the brief instrumental introduction uses the chords I – IVm (E to A minor), which is hardly typical—at least if, like me, you have your roots firmly planted in the folk/rock tradition. There’s more substance to the music than you’d think.

How did Hanks and company pull that off? For one thing, while the instrumentation and overall sound puts it squarely in the ’60s, the song is not the four-chord masterpiece one might expect. The chord progressions are more sophisticated than those of the average rock-and-roll song of the period. Even the brief instrumental introduction uses the chords I – IVm (E to A minor), which is hardly typical—at least if, like me, you have your roots firmly planted in the folk/rock tradition. There’s more substance to the music than you’d think.

Then there’s the fact that the song never does tell us exactly what is “that thing you do”—what makes the girl so irresistible. We know she does it, we know the singer can’t live without it, we know he can’t stand her doing it with “someone new”; but we don’t get anything specific. It’s one of those fruitful ambiguities, where leaving something to the imagination is better than being too definite. The listener can picture their own charming trait or mannerism to fill in the gap. The song keeps one guessing.

Finally, the curious contrast between the rather moody, discontented lyrics of a breakup song (“It’s a ballad!”) and the bright, up-tempo sound and dance beat creates another kind of tension that continues to make “That Thing You Do” more interesting than the unsophisticated setting would suggest. That contrast, in a way, reflects the tone of the whole story. There’s lots of enthusiasm, but it burns out; we do get a happy ending, but not the kind of easy victory as in the battle-of-the-bands stories.

Extended Cuts and Deleted Scenes

As the movie’s Wikipedia article indicates, the longer “extended” version fills out the story in several ways. We get more of Guy’s backstory: for instance, he’s old enough to have been in the Army, which may explain why he’s more mature than the other boys in the band. We see more of his relationship with his original girlfriend Tina, and how that relationship unravels (freeing him to link up with Faye). Other relationships are also followed up in more detail, as with the bass player and one of the girl-group “Chantrellines.” At the end, it’s clear that Guy gets a new job as a radio DJ on the West Coast, which puts him in a better position (with a steady job) to marry Faye, and also puts him on track for a musical career.

However, none of these elaborations of the basic storyline are really necessary. The theatrical version of the movie does fine without them. The extra time for these digressions does alter the pace of the story: my impression on viewing the extended version was that the experience was slower and more leisurely than with the original, shorter version. The shorter cut’s brisk pace seemed to better express the bewildering swiftness of the Wonders’ sudden success and equally sudden collapse. In that respect, I’m inclined to think that in the future, I’ll stick to the original version. Conciseness can be a virtue.

However, none of these elaborations of the basic storyline are really necessary. The theatrical version of the movie does fine without them. The extra time for these digressions does alter the pace of the story: my impression on viewing the extended version was that the experience was slower and more leisurely than with the original, shorter version. The shorter cut’s brisk pace seemed to better express the bewildering swiftness of the Wonders’ sudden success and equally sudden collapse. In that respect, I’m inclined to think that in the future, I’ll stick to the original version. Conciseness can be a virtue.

This parallels my usual reaction to the deleted scenes we often find in a DVD release. When I go back and watch the deleted scenes, I can see what they add, and why the original plan for the story would have included them; yet in every case I can recall, I could also see the reason they were deleted—I agreed, in the end, that the extra scenes were better cut from the final product.

It may be that the theatrical version of a movie is generally preferable to the extended “director’s cut” (though I haven’t canvassed enough examples to draw that broad conclusion with any confidence). The exception—naturally—is the extended editions of The Lord of the Rings movies, where the original source material is simply so huge that even three two-hour movies couldn’t do it justice. I’ll always prefer to watch the longer version of LotR, and still lament that it’s too short.

But for TTYD, I’ll recommend the tighter theatrical version—not to mention the soundtrack album.

I LOVE That Thing You Do! It’s full of great quotes and quips and one-liners, plus fun music and quirky characters. It’s nice to know that there are still fans of it out there. I haven’t watched the director’s cut (is that the same as the extended version?), but I heard it didn’t quite keep to the spirit of the original theatrical release. Sadly, it’s hard to find the original version, though I managed to find one for Christmas last year as a gift. ~Beth

LikeLike

Hi Beth! Yes — it’s a family favorite ’round here.

The Blu-ray I picked up actually has both the theatrical version and the extended version — so I can watch either one. Nice to have the option.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really need to get a Blu-ray player. Would save me a ton of hassle, lol.

LikeLike

Yes. Not only does the picture actually look better (depending on your screen size, of course) — I think it’s getting harder to find plain DVDs of new movies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Seeing a song come together or watching a dance/cheer/music competition can always entertain. Speaking as a writer, though, so much harder for a movie to show a story coming together. Somehow, the visuals of somebody sitting alone, typing slowly, stopping to think, then eyes lighting up and starting to type furiously just doesn’t appeal to the average film fan… 😉

LikeLike

Heh — yes. Partly it’s that writing tends to be a solitary occupation — the action is all internal, whether the envisioned author is hammering at a computer or frantically wielding a quill pen. Partly it’s that the writing of the story doesn’t involve *performing* it: the reading isn’t experienced at the same time as the writing, unlike with music or dance.

There may be compromises, though. I thought “Shakespeare in Love” did a good job of honoring the writer’s craft, interspersing composition moments with actual performances of the scenes (it helps that he’s writing a play), and even reading passages aloud to the enraptured Viola.

The dynamism of writing might also come across if it were a collaboration. Weren’t there some pretty good scenes of the characters developing skits and one-liners in the old Dick Van Dyke Show?

LikeLike

This is where my enormous preference for reading over watching reveals itself. I haven’t seen that movie, and only a few bits of the Dick Van Dyke Show. I’ll have to take your word for it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmm, you’ve got me interested, Rick! just checked out the trailer and TTYD is now on my films to watch list. I do get hooked by creative performance success stories, seeing the development and the outcome!

LikeLike

Lynne — Glad to hear it! Hope you like the movie as much as I do.

LikeLike

I haven’t seen this movie, but I’m adding it to my queue now!

I think the only movie I’ve seen (aside from the LOTR trilogy, where I completely agree with you) where I thought the movie would have been improved by the inclusion of the some of the deleted scenes was Bulletproof Monk. The fact that one and only one immediately stands out in my mind definitely suggests that it’s a rare phenomenon!

LikeLike

Cool!

I haven’t seen Bulletproof Monk — is that a good one?

LikeLike

I would say so-so. I went and looked at my LJ – I don’t review movies, but I try to write something about every movie I see. Here’s what I wrote (in September 2012) about Bulletproof Monk:

“Bulletproof Monk was okay; I was expecting more, but what we got wasn’t bad. I wanted more about, you know, the actual title character (Chow Yun Fat) and less about the American street kid (Seann Something Something) he takes under his wing, blah blah blah. It had some nice moderately philosophical moments and some pretty good fights. The villains were great, especially the evil dude’s evil daughter. The DVD came with the deleted scenes, including a few that would have made the ending far more complex and interesting.”

One of my friends commented dryly, “I see ‘Seann Something Something’ was really memorable in his role. ;)”

LikeLike

Memorable in his role, heh!

The mentor’s backstory is something we don’t always get to see — though it can be hard for that earlier story to live up to the image the mentor projects when all s/he has to do is be mysterious and wise.

It was interesting to see a young Moiraine in Robert Jordan’s _New Spring_; but the younger version didn’t seem quite adequate to the brilliant, powerful, kick-ass older woman we all know and love.

I haven’t yet caught up with the Crimes of Grindelwald — so I can’t say as to the younger Albus Dumbledore.

LikeLike