The Crucible

I don’t see a lot of stage plays. Generally I wait for the movie version to come out. (Which took quite a while in the case of Les Miserables—though in that case I actually did see the play twice on stage.)

Recently, however, I had occasion to see a performance of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (1953), by the Lumina Theatre Company: my son was in the cast. (Portraying one of the villains; and he did it very well!) The Crucible is one of those plays that many people have been exposed to, often as a high-school reading assignment. But I had managed to miss either seeing or reading the play, up to now. It was a powerful experience: a moving story, well performed by Lumina.

Recently, however, I had occasion to see a performance of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (1953), by the Lumina Theatre Company: my son was in the cast. (Portraying one of the villains; and he did it very well!) The Crucible is one of those plays that many people have been exposed to, often as a high-school reading assignment. But I had managed to miss either seeing or reading the play, up to now. It was a powerful experience: a moving story, well performed by Lumina.

As is well known, The Crucible is set in the period of the Salem witch trials in 1692-93. It’s also an allegory for the McCarthy hearings on Communism (1953-54) during the “Red Scare.” I don’t know whether the term “witch hunt” for such persecution-by-investigation originated with Miller’s play; the phrase has certainly seen a lot of mileage since.

At the moment, however, I’m not interested in the politics or the story, but in an aspect of the staging that caught my attention, and reminded me of a couple of dramaturgically similar cases I’ve seen before.

The Austere Stage

I’m even less of an expert on the stage than I am on movies; but even I, as a layman, was struck by the simplicity of the stage setting. There was no backdrop; walls and ceiling were black. A series of tall panels vaguely suggesting a forest marked the left and right sides of the stage. The performance depended on adroit use of a few simple props—a bed, a table, some cooking utensils—to indicate whether we were seeing a bedroom, a kitchen, or the anteroom of a court.

I’m even less of an expert on the stage than I am on movies; but even I, as a layman, was struck by the simplicity of the stage setting. There was no backdrop; walls and ceiling were black. A series of tall panels vaguely suggesting a forest marked the left and right sides of the stage. The performance depended on adroit use of a few simple props—a bed, a table, some cooking utensils—to indicate whether we were seeing a bedroom, a kitchen, or the anteroom of a court.

Apparently this is a “thing.” As people with a wider background in theatre probably know, there’s a style called the “Black Box Theater” (which was literally the name of the particular theatre where this performance occurred). Wikipedia says: “A black box theater (or experimental theater) consists of a simple, somewhat unadorned performance space, usually a large square room with black walls and a flat floor, which can be used flexibly to create a stage” (emphasis and link omitted).

It seemed to me that in The Crucible this stark environment served well to focus our attention on the characters and their interactions, rather than on the surroundings. Actors wore period clothing, but otherwise there was no strong sense of historical setting. That seems especially appropriate in a case where the author intends us to see not only the events happening in a particular time and place, but also their analogue in 1950s American politics, or other situations.

That reflection reminded me of a couple of other times when I’ve seen a show that worked better on a relatively bare stage than in a movie. As a rule, the movie version of a show like Oklahoma! or The Sound of Music has the advantage of being able to present the setting with greater realism and vividness: we can actually see the Midwestern plains or the Austrian mountains. And today’s CGI technology can set before us almost any imaginable background. But sometimes we don’t want to emphasize the particular setting.

Man of La Mancha

Man of La Mancha (1965), with a book by Dale Wasserman, lyrics by Joe Darion, and music by Mitch Leigh, is derived from Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote. The play is not intended as a complete adaptation of the novel; one might, in fact, argue that the authors make use of selected parts of the novel to build a story whose effect is quite different from what Cervantes intended (something I want to address at a later date). It was the Wasserman-Darion-Leigh musical that strongly influenced me, starting in high school.

Man of La Mancha (1965), with a book by Dale Wasserman, lyrics by Joe Darion, and music by Mitch Leigh, is derived from Cervantes’ novel Don Quixote. The play is not intended as a complete adaptation of the novel; one might, in fact, argue that the authors make use of selected parts of the novel to build a story whose effect is quite different from what Cervantes intended (something I want to address at a later date). It was the Wasserman-Darion-Leigh musical that strongly influenced me, starting in high school.

The musical begins with a frame story: Cervantes himself is in prison, waiting to be examined by the Inquisition. To pacify and intrigue the other prisoners, he draws them into an impromptu enactment of scenes from the novel (Don Quixote) he is writing. The story-within-a-story focuses on Quixote’s absurd, yet ennobling, idealism in conflict with the brutal realism of everyone else except his loyal servant Sancho Panza; and on how Quixote’s eccentric view of the world influences a young woman at an inn, a prostitute named Aldonza, whom he insists on seeing as the noble lady Dulcinea. As the inner story concludes, back in the dungeon Cervantes is called up to face the Inquisition. He now ascends to meet his fate with courage as the rest of the cast reprises “The Impossible Dream.”

I’ve seen Man of La Mancha on stage twice, once in 1970 with Howard Keel, and again with the Shakespeare Theatre Company in 2015. The 1970 production took place in a theatre-in-the-round, which eliminated the use of any backdrops at all; though, as I recall, there was a long, impressive stairway that could be lowered from the ceiling to illustrate the opening and closing of the dungeon. This comports with Wikipedia’s description of the original production:

I’ve seen Man of La Mancha on stage twice, once in 1970 with Howard Keel, and again with the Shakespeare Theatre Company in 2015. The 1970 production took place in a theatre-in-the-round, which eliminated the use of any backdrops at all; though, as I recall, there was a long, impressive stairway that could be lowered from the ceiling to illustrate the opening and closing of the dungeon. This comports with Wikipedia’s description of the original production:

The musical was performed on a single set that suggested a dungeon. All changes in location were created by alterations in the lighting, by the use of props supposedly lying around the floor of the dungeon, and by reliance on the audience’s imagination.

The Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production was not theatre-in-the-round, but used a similarly spare set, with a catwalk above and again, a stairway that could be raised and lowered. Both the 1970 and the 2015 iterations were excellent and moving presentations of the stage play.

The movie version of the musical (1972) was disappointing. It didn’t help that the producers cast Peter O’Toole and Sophia Loren in the leading roles, since neither of them could really sing—although visually Loren was a perfect Aldonza. But even aside from the musical issues, the screen adaptation, depicting a green countryside (with windmills) and the inn where Aldonza works, seemed distinctly less effective than the stage version.

Why? Eventually I concluded that the whole point of the show—competing and radically different visions of the world—was undermined by the fact that the movie used real landscapes. Viewing the story, one has to keep in constant tension the world as Quixote sees it (giant, castle, lady, varlets) and the world as everyone else sees it (windmill, inn, sullen and degraded woman, rough and violent muleteers). In addition, with the frame story, it’s also necessary to keep in mind that this is theoretically being acted out by prisoners of the Inquisition in a dungeon.

Why? Eventually I concluded that the whole point of the show—competing and radically different visions of the world—was undermined by the fact that the movie used real landscapes. Viewing the story, one has to keep in constant tension the world as Quixote sees it (giant, castle, lady, varlets) and the world as everyone else sees it (windmill, inn, sullen and degraded woman, rough and violent muleteers). In addition, with the frame story, it’s also necessary to keep in mind that this is theoretically being acted out by prisoners of the Inquisition in a dungeon.

So in this story, we have to keep three levels of realities before us at once. But with the movie, the director had to commit to one or the other vision: either film an inn and leave the castle imaginary (and the dungeon tacit), or vice versa. Unless the movie simply filmed a production of the play—a compromise which rarely satisfies anyone. In this particular case, the greater realism of the movie version actually blunted the effect of the story.

Godspell

The 1960s-1970s were the era of what one might call big-concept musicals—at the opposite end of the spectrum from the wholly frivolous musical comedies of the 1930s-1940s. Like the folk Mass of the same period, Godspell (1971) sought to convey a fresh view of Christianity by putting it in the form of popular music and styles.

The 1960s-1970s were the era of what one might call big-concept musicals—at the opposite end of the spectrum from the wholly frivolous musical comedies of the 1930s-1940s. Like the folk Mass of the same period, Godspell (1971) sought to convey a fresh view of Christianity by putting it in the form of popular music and styles.

The play describes itself as “A musical based upon the Gospel according to St. Matthew,” though it doesn’t actually confine itself to that Gospel. It’s structured as a series of musical numbers with skits illustrating classic parables, bookended by stylized, minimalist episodes representing the initial calling of disciples and the Passion. The characters, except for Jesus and perhaps John and Judas, are non-Biblical, and the entire cast is dressed in colorful informal clothes reminiscent of the “hippies” of that period.

I saw the play at least once or twice back in the 1970s, though I don’t recall the particular venues. Like Man of La Mancha, it was presented with a minimum of props and without backdrops. The focus was on the music and the actions of the characters. It wasn’t individual personalities or character development one focused on; the characters themselves are somewhat arbitrary, without history or backstory. Rather, it appears they were deliberately designed to represent a group of Everypeople.

The modern style of the music, together with the lack of time and place cues (as in The Crucible) and the randomness of the costuming, serve to lift the play out of its historical place in first-century culture. That abstraction made it more accessible to contemporary young people. (Whether it still has that effect now, fifty years later, I can’t say.) Rather than being distracted by the antique ambiance of robes and horses and Roman soldiers, the audience could perceive the Gospel stories in a new light.

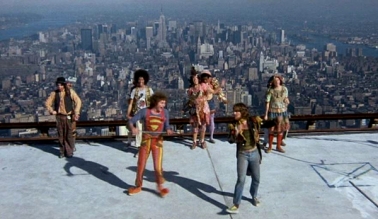

As with Man of La Mancha, the popular stage play was promptly followed up by a movie version (1973). The producers and director chose to set the movie’s activities in New York City. The characters’ antics are seen against the Brooklyn Bridge, Times Square, the top of a World Trade Center tower, and other well-known New York locales. Wikipedia observes: “While the play requires very little stage dressing, the film places emphasis on dramatic location shots in Manhattan.”

As with Man of La Mancha, the popular stage play was promptly followed up by a movie version (1973). The producers and director chose to set the movie’s activities in New York City. The characters’ antics are seen against the Brooklyn Bridge, Times Square, the top of a World Trade Center tower, and other well-known New York locales. Wikipedia observes: “While the play requires very little stage dressing, the film places emphasis on dramatic location shots in Manhattan.”

In this case, the musical aspect of the movie was fine. At least one critic considered the movie soundtrack better than the original stage cast album. Yet, again, it seemed to me that overall the movie was not quite as effective as the stage play. The realistic modern setting did not improve upon the minimalist furnishing of the stage play. I concluded that, if the goal is to abstract the essence of the Gospels as universally applicable, regardless of time or place, the movie setting isn’t an advantage: it lifts the action out of first-century Palestine, but ties it back down to contemporary New York. The very spare, austere stage set helps the viewer make that abstraction.

Conclusion

I’m a great fan of CGI, and look forward to seeing a full-fledged dramatic presentation using virtual reality (VR). Modern technology allows us to present almost any science fiction or fantasy setting—things we never see in real life—realistically enough for us to suspend disbelief. But when we don’t want realism, simplicity may be a better approach. Even in our high-tech age, the plain theatrical stage has its uses.