Introduction

Even though science fiction is often focused on the future, its assumptions are tied to the present.

In some respects this is obvious. A story about the near future can become dated by history itself. Every SF story prior to 1969 that describes the first moon landing in detail (happy 51st anniversary, last week!) is obsolete. And every story that predicted a smooth reach out into colonizing the solar system directly after that first landing, unfortunately, is also defunct. Stories can also be rendered unbelievable by scientific advance: all the delightful tales based on a habitable Venus or Mars are gone with the, er, vacuum.

In some respects this is obvious. A story about the near future can become dated by history itself. Every SF story prior to 1969 that describes the first moon landing in detail (happy 51st anniversary, last week!) is obsolete. And every story that predicted a smooth reach out into colonizing the solar system directly after that first landing, unfortunately, is also defunct. Stories can also be rendered unbelievable by scientific advance: all the delightful tales based on a habitable Venus or Mars are gone with the, er, vacuum.

But there’s also a subtler way. Even though F&SF specialize in examining our assumptions about the universe, the assumptions that seem plausible shift over time. Fashions change. To take a heartening example: SF stories from the late 1940s and the 1950s tended to take it for granted that there would shortly be a nuclear world war. (Hence it’s spot-on characterization when the 1955 version of Doc Brown in “Back to the Future” accepts Marty’s recorded appearance in a hazmat suit as logical because of the “fallout from the atomic wars.”) But for over seventy years, we’ve managed to avoid that particular catastrophe.

One assumption that’s always intrigued me is whether we are likely to meet people like ourselves—and I mean, exactly like ourselves—on another planet. If we discovered an Earthlike planet of another sun, might we climb down the ladder from our spaceship to shake hands with a biologically human alien?

Not Really Alien

I’m talking about a “convergent evolution” hypothesis—the notion that the human species might have developed independently more than once. And, incidentally, the standard biological definition of “species” as “interfertile” (a more precise definition can be found on Wikipedia) is what I’m using here; because, obviously, one of the potential uses of the assumption in a story is to make possible a romance between two characters from different worlds, and romance is not unrelated to sex and reproduction.

So we want to set aside, to begin with, a class of stories in which people from different planets are all human because they have a common ancestry. For example, in Jack Williamson’s classic space opera The Cometeers (1936), Bob Star finds his true love Kay Nymidee among the human subjects of the decidedly nonhuman masters of an immense assemblage of space-traveling planets, the “comet.” But the reason there are human beings present is that a research ship from Earth was captured by the Cometeers long ago, and these are the descendants of the crew.

So we want to set aside, to begin with, a class of stories in which people from different planets are all human because they have a common ancestry. For example, in Jack Williamson’s classic space opera The Cometeers (1936), Bob Star finds his true love Kay Nymidee among the human subjects of the decidedly nonhuman masters of an immense assemblage of space-traveling planets, the “comet.” But the reason there are human beings present is that a research ship from Earth was captured by the Cometeers long ago, and these are the descendants of the crew.

It’s not uncommon for the inheritance to work the other way around. David Weber’s “Mutineers’ Moon” (1991) starts with the eye-opening assumption that our Moon is actually a long-inert giant spaceship—and reveals that the humanity of Earth is descended from the original crew members of that spaceship. Thus, it’s perfectly plausible when hero Colin MacIntyre falls for a preserved member of the original crew; they’re from the same stock. Similarly, in at least the original 1978 version of Battlestar Galactica, the human survivors of the “rag-tag fugitive fleet” are human because Earth itself was one of their original colonies, which apparently fell out of touch.

The Era of Planetary Romance

In the early days of modern SF—say, from about 1912 through the 1930s—it was commonly assumed that the answer was yes: human beings (with minor variations) might be found independently on other planets. Arguably, this may have been because the early planetary romances—melodramas set on exotic worlds, heavy on adventure and love stories—were less interested in science than in plot devices. But biology was less advanced in those days; recall that DNA was not identified as the basis of genetic inheritance until 1952. It’s easy to forget how little we knew about things we take for granted today, even in relatively recent periods.

A classic early case is that of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom. In A Princess of Mars (1912), Earthman John Carter is transported by obscure means to Mars, called by its inhabitants “Barsoom.” Those inhabitants include the nonhuman “Green Martians,” but also people identical to humans in several colors, particularly the “Red Martians” among whom Carter finds his lady-love, Dejah Thoris. As a Red Martian, Dejah is human enough for Carter to mate with, and they have a son, Carthoris, thus meeting the “interfertile” criterion.

To be sure, the biology here is a little mysterious. Dejah looks entirely human, and even, to borrow a Heinlein phrase, “adequately mammalian” (see, for example, Lynn Collins’ portrayal in the loosely adapted movie John Carter (2012)). But Martians don’t bear their young as Earth-humans do; they lay eggs, which then develop for ten years before hatching. It’s not easy to imagine the genetics that could produce viable offspring from an individual whose genes direct live birth and one whose genes result in egg-laying. But that didn’t stop Burroughs.

E.E. Smith, whose initial SF writing goes back just about as far as that of Burroughs, was willing to accept this trope as well. In The Skylark of Space (published 1928, but written between 1915 and 1921), our intrepid heroes travel to a planet inhabited by two nations of essentially human people—although the double wedding in the story does not involve any interplanetary romances, but is between two pairs of characters from Earth. Smith’s later Lensman series (1948-1954), which features one of the most diverse arrays of intelligent creatures in SF, also allows for apparently interfertile humans from a variety of planets. My impression is that this sort of duplication was also true of some of the nonhuman species in the Lensman unverse—there might be, say, Velantian-types native to planets other than Velantia.

This approach wasn’t universal in old-time SF. The more scientifically-minded John W. Campbell’s extraterrestrial character Torlos in Islands of Space (1930) was generally humanoid in form, but quite different in makeup: his iron bones, for instance. It’s been argued that a roughly humanoid form has some advantages for an intelligent species, and hence that we might find vaguely humanoid aliens on different planets—though this is pure speculation. But “humanoid” is a far cry from biologically human.

We see some persistence of this tradition into the second half of the twentieth century. Marion Zimmer Bradley’s iconic planet Darkover, for instance (first novel published 1958), is populated by the descendants of Terran humans from a colony ship and also by the elf-like indigenous Chieri, who, despite minor differences like six fingers and golden eyes, not to mention the ability to change sex at will, have interbred with the Terran immigrants.

We see some persistence of this tradition into the second half of the twentieth century. Marion Zimmer Bradley’s iconic planet Darkover, for instance (first novel published 1958), is populated by the descendants of Terran humans from a colony ship and also by the elf-like indigenous Chieri, who, despite minor differences like six fingers and golden eyes, not to mention the ability to change sex at will, have interbred with the Terran immigrants.

An interesting variation can be seen in Julian May’s Saga of Pliocene Exile (first story published in 1981). When modern humans are sent on a one-way trip into the distant past, they are enslaved by the Tanu, aliens from another galaxy who have settled on Earth. The story indicates that the Tanu were specifically searching for a place where the local gene pool was similar to theirs—which might also account for why they came all the way from another galaxy (also a somewhat antique trope) to get here.

It’s slightly odd that, even where basically identical human beings turn up on other planets, other animals never seem to be similarly duplicated. On Burroughs’ Barsoom, one doesn’t ride horses, but thoats; is menaced not by tigers, but by banths; and keeps a calot, not a dog, as a pet. In a planetary romance or science fantasy setting, one is less likely to see Terran-equivalent fauna than parallel creatures with exotic names and slight differences—whence the SF-writing gaffe “Call a Rabbit a Smeerp” (see TV Tropes and the Turkey City Lexicon).

At the Movies

The all-too-human trope is carried on into the present day in video media—movies and TV. Again, this may be partly because the science is often subordinated to the plot; but the cost and difficulty of putting convincing nonhuman characters on-screen is surely another factor. Filmmakers’ ability to depict exotic creatures, however, has changed immensely in the last forty years, to a point where almost any imaginable creature can be created if the budget is sufficient. Thus, the original Star Trek series of the 1960s stuck largely to slightly disguised humanoid aliens, perhaps relying on the ‘universal humanoid’ hypothesis mentioned above, while later series were able to branch out a bit. Similarly, the Star Wars movies could readily give us nonhuman characters like Jabba the Hutt, Chewbacca, and C3PO; they, too, grew in variety as the capabilities of CGI and other techniques expanded.

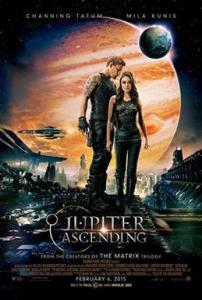

Still, it may be harder for us to adjust to interactions among characters where we can see their nonhumanity, rather than just reading about it. So we still tend to see extraterrestrial humans on-screen. The Kree in Captain Marvel (2019), for example, are indistinguishable from humans—an actual plot point, since this makes it possible for Yon-Rogg to tell Carol that she’s an enhanced Kree rather than a kidnapped human. The Kree do have blue blood, in the movie; it’s not clear what kind of biological difference (hemocyanin?) might result in that feature. We also see a number of alien humans in Jupiter Ascending (2015), though I think of that tale as a deliberate throwback to pulpish science fantasy or planetary romance.

Still, it may be harder for us to adjust to interactions among characters where we can see their nonhumanity, rather than just reading about it. So we still tend to see extraterrestrial humans on-screen. The Kree in Captain Marvel (2019), for example, are indistinguishable from humans—an actual plot point, since this makes it possible for Yon-Rogg to tell Carol that she’s an enhanced Kree rather than a kidnapped human. The Kree do have blue blood, in the movie; it’s not clear what kind of biological difference (hemocyanin?) might result in that feature. We also see a number of alien humans in Jupiter Ascending (2015), though I think of that tale as a deliberate throwback to pulpish science fantasy or planetary romance.

I keep wanting to cite the fictional novel written by George McFly as shown in the closing scenes of Back to the Future, “A Match Made in Space,” since the cover seems to suggest an interplanetary romance (and one thinks of George as a nerdy romantic); but it isn’t actually clear whether that’s the case. All we have to go on is the title and the cover, and that could just as easily depict a match between two humans, fostered by an alien matchmaker (or vice versa).

I keep wanting to cite the fictional novel written by George McFly as shown in the closing scenes of Back to the Future, “A Match Made in Space,” since the cover seems to suggest an interplanetary romance (and one thinks of George as a nerdy romantic); but it isn’t actually clear whether that’s the case. All we have to go on is the title and the cover, and that could just as easily depict a match between two humans, fostered by an alien matchmaker (or vice versa).

The Modern Era

We don’t see nearly as many extraterrestrial humans in modern SF, and for good reason.

The more we understand about genetics, the less likely it seems that another human species, so closely similar as to be interfertile, could evolve independently. What we know about evolution suggests that there are just too many random chances along the way—cases where the prevailing mutations might have turned out differently. Even if we assume that humanoid form is probable, why not have six fingers, or hemocyanin rather than hemoglobin? While I’m not well enough educated in biology to venture any actual probabilities, I think our growing sense of the complexity of the human body and its workings, over the last seventy years or so, has simply made it seem vanishingly unlikely that an independently evolved intelligence would come out that close to the human genotype.

For example, the scientifically-minded Arthur C. Clarke depicted a galaxy in which each intelligent species, including humans, was unique: The City and the Stars (1956, developed from an earlier story published in 1948). In one of the unused story fragments he wrote while working on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), his hero, well along on his journey into mystery, thinks:

He did not hesitate to call them people, though by the standards of Earth they would have seemed incredibly alien. But already, his standards were not those of Earth; he had seen too much, and realized by now that only a few times in the whole history of the Universe could the fall of the genetic dice have produced a duplicate of Man. The suspicion was rapidly growing in his mind—or had something put it there?—that he had been sent to this place because these creatures were as close an approximation as could readily be found to Homo sapiens, both in appearance and in culture. (Clarke, The Lost Worlds of 2001, ch. 39, p. 220)

Contemporary SF writers who are really adept at building interesting and coherent aliens—David Brin and Becky Chambers, to name two of the best—give us a wide range of wildly exotic creatures from other planets, but not humans.

If we are still fond of the idea of interplanetary romance, we might find a possible work-around in the shapeshifter. The Tymbrimi female Athaclena in Brin’s The Uplift War (1987) uses her species’ unusual abilities to adjust her appearance closer to that of a human female—but of course she has an entirely different genetic heritage, as that ability itself demonstrates. The result wouldn’t meet our criterion of interfertility, no matter how close the similarity in physical structure. To adjust one’s genes in the same way would be another order of change altogether.

If we are still fond of the idea of interplanetary romance, we might find a possible work-around in the shapeshifter. The Tymbrimi female Athaclena in Brin’s The Uplift War (1987) uses her species’ unusual abilities to adjust her appearance closer to that of a human female—but of course she has an entirely different genetic heritage, as that ability itself demonstrates. The result wouldn’t meet our criterion of interfertility, no matter how close the similarity in physical structure. To adjust one’s genes in the same way would be another order of change altogether.

The 1984 movie Starman, in a way, plays off this idea. The alien in this case is apparently an entity made of pure energy, without a physical structure of its own. Using hair from the female lead’s deceased husband, it creates a new body with a human genetic structure. The two do, eventually, prove to be interfertile. If we’re willing to accept the notion of an energy being in the first place, this approach is actually more plausible than, say, mating with the oviparous Dejah Thoris.

The 1984 movie Starman, in a way, plays off this idea. The alien in this case is apparently an entity made of pure energy, without a physical structure of its own. Using hair from the female lead’s deceased husband, it creates a new body with a human genetic structure. The two do, eventually, prove to be interfertile. If we’re willing to accept the notion of an energy being in the first place, this approach is actually more plausible than, say, mating with the oviparous Dejah Thoris.

If one were writing a SF story today, it would be rash to assume that Earthborn characters could run across independently evolved humans elsewhere. The idea may not be entirely inconceivable. But it’s out of fashion for good reasons. Attractive as the notion of interplanetary romance may be, at this point we’d best confine it to the kind of case noted above, where some common ancestry—no matter how far-fetched—can account for the common humanity.