Introduction

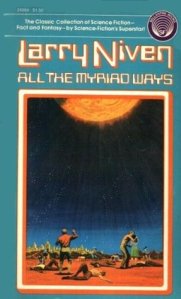

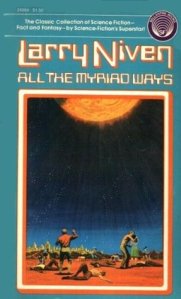

I set out to do an analytical essay on Three Theories of Time Travel—until I realized that Larry Niven’s astute and entertaining brief article “The Theory and Practice of Time Travel” (1971) had already covered those theories pretty well. (You can find that article in Niven’s All the Myriad Ways, and a couple other locations.) So I decided instead to comment on how they’re used in Avengers: Endgame, which seems to invoke at least two and possibly three different theories.

I set out to do an analytical essay on Three Theories of Time Travel—until I realized that Larry Niven’s astute and entertaining brief article “The Theory and Practice of Time Travel” (1971) had already covered those theories pretty well. (You can find that article in Niven’s All the Myriad Ways, and a couple other locations.) So I decided instead to comment on how they’re used in Avengers: Endgame, which seems to invoke at least two and possibly three different theories.

Maybe I’d have been better off sticking with the original plan; this post has turned out to be considerably longer than I’d planned.

Endgame came out on April 26, 2019, and was released on disc August 13, so it’s still new enough at this writing that I should issue a

I’m not going to address the mechanics of how one might travel into the past—whether via Tipler machines, or wormholes, or simply thinking oneself into the past à la Jack Finney. (Endgame manages it via what the movies refer to as the “Quantum Realm,” which is completely incoherent in one way but rather fascinating in another—a side issue I won’t go into here.) I’m interested in what happens if you let causality turn back on itself. I can think of three main ways of handling the question of changing the past. Each has its pros and cons, from a storytelling point of view.

“Make It Didn’t Happen”

First, let’s suppose we can change the past (and, by extension, the present and future). The idea arises because we often wish we could go back and undo something—either our own actions, or the broader course of history. Niven observes, “When a child prays, ‘Please, God, make it didn’t happen,’ he is inventing time travel in its essence.” He goes on to note, “The prime purpose of time travel is to change the past; and the prime danger is that the Traveler might change the past.” These twin aspects of the idea generate plot tensions and conflicts immediately, on both a personal and a historical scale, so it’s not surprising they’re so popular.

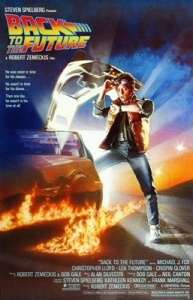

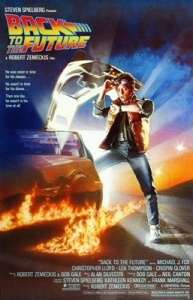

The most familiar example, of course, is Back to the Future (1985-1990). In the three movies, Zemeckis played several variations on the idea of making history come out differently. The cultural reference is so well-known that Marvel was able to riff off it for a comic moment in Endgame. Scott Lang, the young and relatively naïve Ant-Man, says they’ll be okay if they obey the ‘rules of time travel’ (at about 0:35). Tony Stark, the all-round genius of the Marvel movies, derides Scott for having gotten his “rules” from BTTF, and proceeds to shoot the notion down as hopelessly unscientific.

The most familiar example, of course, is Back to the Future (1985-1990). In the three movies, Zemeckis played several variations on the idea of making history come out differently. The cultural reference is so well-known that Marvel was able to riff off it for a comic moment in Endgame. Scott Lang, the young and relatively naïve Ant-Man, says they’ll be okay if they obey the ‘rules of time travel’ (at about 0:35). Tony Stark, the all-round genius of the Marvel movies, derides Scott for having gotten his “rules” from BTTF, and proceeds to shoot the notion down as hopelessly unscientific.

And Tony’s right, in the sense that building a theory of time travel purely on the assumptions made in fictional stories is silly. We don’t know what would happen if it were possible to change the past; we haven’t done it. That would make time travel really dangerous if it could be attempted in real life. On the other hand, that same lack of knowledge leaves a wide field open for the fiction writer. We can make whatever assumptions we like, as long as they’re consistent. We can imagine that you can only go back in time a certain distance, at a certain geographical location, as in Julian May’s Saga of Pliocene Exile (1981-84). We can imagine that the transition requires vast energies, as in Arthur C. Clarke’s story “Technical Error” (1950). Or we can invoke the imaginary “Pym particles” of Ant-Man lore and time-travel at will.

This first theory of time travel generates the paradoxes we know and love. We have the “grandfather paradox,” in which an effect removes its own cause. (I go back in time and kill my grandfather.) We have what Wikipedia calls the “ontological paradox,” in which an effect becomes its own cause. (I go back but my grandfather fails to show up, so I marry my grandmother instead and name my son after my dad…) I talked about these a bit in a 2016 post on the TV series Timeless.

One thing that’s not always obvious is that the idea of changing the past requires a second time dimension. There’s the familiar one that’s typically represented by a “timeline,” a one-dimensional line ordering events from past to future. But if someone changes the past, then the old line has to be replaced by a new one: imagine a second timeline lying next to the first. Every time a change is made, another timeline gets added. The set of lines forms a plane, extending through a second dimension, in which each new timeline happens after (in some Pickwickian sense) the last. Otherwise, it wouldn’t make any sense to say that we’d changed history. Marty can’t rejoice in having “fixed” his family unless the new timeline succeeds the first, just as events along the timeline succeed each other. Hence, a second time dimension, to accommodate the sequence of timelines. (This may, or may not, be related to what TV Tropes calls “San Dimas Time,” a reference from Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989).

As a narrative device, the chance to change the past creates suspense. But it only works if you don’t look too closely. The author has to stage-manage things carefully so that changes of all sorts don’t start happening in all directions, and this means that time travel must be rare. If we imagine a period of hundreds or thousands of years, during which people invent time machines every so often and start changing the past, it would become impossible to make sense of what was happening. Different changes, each with their rippling “butterfly effects,” would take place, one after another—or even at the same, er, time. (I tried playing around with that idea in an as-yet-unpublished story called Getting to Gettysburg.) So I’m skeptical about stories based on letting time travel become routine, as in “Time Patrol” scenarios or Asimov’s The End of Eternity.

Avengers Disassemble

Does Endgame, after all Tony’s disclaimers, involve changing the past? Maybe not; but it’s hard to see how the story can avoid it.

The screenwriters chose to set themselves an interesting dilemma that makes the simple time-travel solution (go back and kill Thanos) unusable. When the time-travel possibility arises, five years have passed since the Snap, in which Thanos killed off half the people in the universe. Life has gone on. Tony and Pepper, for example, have an adorable little girl. But eliminating the Snap would also eliminate Tony’s little daughter Morgan, along with everything else that’s happened since. That’s unacceptable (at least to Tony). So the Avengers are not trying to avert the Snap; instead, they want to bring back, in the present time, all those who disintegrated.

The screenwriters chose to set themselves an interesting dilemma that makes the simple time-travel solution (go back and kill Thanos) unusable. When the time-travel possibility arises, five years have passed since the Snap, in which Thanos killed off half the people in the universe. Life has gone on. Tony and Pepper, for example, have an adorable little girl. But eliminating the Snap would also eliminate Tony’s little daughter Morgan, along with everything else that’s happened since. That’s unacceptable (at least to Tony). So the Avengers are not trying to avert the Snap; instead, they want to bring back, in the present time, all those who disintegrated.

The reason they have to go into the past is to retrieve the six Infinity Stones, which Thanos destroyed after the Snap. The Avengers will need to use the Stones for a Snap of their own to bring back all the people Thanos destroyed. But in order to avoid changing the past, they will have to put the Stones back in their earlier times after they’ve been used. This is a clever idea, but it’s going to be really tricky to execute in practice, as we’ll discuss below.

It’s Already Happened

Meanwhile, the business of a second time dimension may make us start to wonder about the whole idea of changing the past. Maybe we’ve forgotten to take into account the integrity of the original time dimension. After all, if something happened in the past, it has already happened. The effects of past events should be baked into the present that follows from them. If I go back to 1800 and leave a hidden time capsule, let’s say, I should be able to dig it up in 2019. You might say that the change I wish to make has already taken place.

But it follows that if I can find the evidence in the present, then I know the event occurred in the past. (That’s what “evidence” means.) If I find the time capsule, I know that it was buried. This may allow me to predict or “retrodict” my future changes to the past on the basis of what’s known now. If I find the time capsule, I know I’m going to bury it—or someone else will. A key scene in Kate and Leopold (2001) relies on just such a discovery about a future event that changes the past. (Have we mixed up the tenses enough yet?) Bill and Ted makes even more comically inventive use of this aspect.

But it follows that if I can find the evidence in the present, then I know the event occurred in the past. (That’s what “evidence” means.) If I find the time capsule, I know that it was buried. This may allow me to predict or “retrodict” my future changes to the past on the basis of what’s known now. If I find the time capsule, I know I’m going to bury it—or someone else will. A key scene in Kate and Leopold (2001) relies on just such a discovery about a future event that changes the past. (Have we mixed up the tenses enough yet?) Bill and Ted makes even more comically inventive use of this aspect.

But on this theory, the event in the past isn’t really a change. It was always that way. The time capsule persisted through all the intervening time. You can’t change the past, because your change is already included in the past we know and thus embedded in the present. As Niven puts it, “any attempt on the part of a time traveler to change the past has already been made, and is a part of the past.”

This approach deprives us of the fun of changing history, but I rather like it. It ensures the timeline remains consistent with itself. In fact, one version of this postulate is referred to as the “Novikov self-consistency principle,” named for Russian physicist Igor Dmitriyevich Novikov. We avoid grandfather paradoxes: we already know I didn’t succeed in traveling into the past and killing my grandfather, because here I am. If I try, something will go wrong. On the other hand, ontological paradoxes are still allowed, as in Heinlein’s classic novella By His Bootstraps (1941). In fact, I tend to think of this as ‘Heinlein’s theory of time travel,’ because he used it extensively—not only in Bootstraps and the even more baffling “—All You Zombies—” (1959), but also in the delightful The Door Into Summer (1957). Of course, Heinlein’s by no means the only writer using a Novikov-type theory.

One reason I like this type of time travel story is that everything fits neatly together, like a puzzle. The fun of the story is in seeing how they’ll fit. In that sense, the enjoyment of you-already-changed-the-past stories resembles that of the Greek tragedies, in which an oracular pronouncement tells what’s going to happen, and the story shows how it happens. No matter how Oedipus tries to avoid the awful future foretold, he can’t. The efforts to avoid the predicted outcome may themselves produce it.

In such a tragedy, where time travel isn’t involved (except to the extent the oracle itself is future information acting on the past), the Greek tragedy tends to suggest that the outcome is determined by some kind of Fate, whether we like it or not. (Niven puts this view under the heading of “determinism.”) But the Novikov-type theory can also be seen as compatible with free will. Even actions freely taken, once they are complete, become part of the fabric of history, not subject to further change afterwards—except to the extent that backward causation via time travel is possible, which alters the whole meaning of “afterwards.”

A subclass of these stories assumes that the time continuum somehow defends itself against change. It may automatically “self-heal” to swallow up minor changes, or all changes: Edison doesn’t invent the light bulb, but someone else does. Or the time stream may simply be designed so that with “fail-safes” that prevent catastrophic causality failures. At the end of The Door Into Summer, the engineer hero seems to be speculating in this direction: if time travel could be used commercially, he thinks,

A subclass of these stories assumes that the time continuum somehow defends itself against change. It may automatically “self-heal” to swallow up minor changes, or all changes: Edison doesn’t invent the light bulb, but someone else does. Or the time stream may simply be designed so that with “fail-safes” that prevent catastrophic causality failures. At the end of The Door Into Summer, the engineer hero seems to be speculating in this direction: if time travel could be used commercially, he thinks,

it will be because the Builder designed the universe that way. He gave us eyes, two hands, a brain; anything we do with them can’t be a paradox. He doesn’t need busybodies to “enforce” His laws; they enforce themselves. (p. 158)

In a modern context, God seems to take over the role of Fate—not by predetermining everything, but by designing the system (i.e., the universe) so nothing can go fatally wrong with causality. Something similar, I think, lies behind the way the time travel “net” portal functions in Connie Willis’s time travel stories. If allowing something through the net would create a paradox, the net simply won’t open—which leads to some tortuous reasoning by the characters as to what is keeping the net from openingaat a particular moment. Something like Providence seems to be at work. The only causal loops allowed are what we might call ‘virtuous loops’—those that work out right.

In a modern context, God seems to take over the role of Fate—not by predetermining everything, but by designing the system (i.e., the universe) so nothing can go fatally wrong with causality. Something similar, I think, lies behind the way the time travel “net” portal functions in Connie Willis’s time travel stories. If allowing something through the net would create a paradox, the net simply won’t open—which leads to some tortuous reasoning by the characters as to what is keeping the net from openingaat a particular moment. Something like Providence seems to be at work. The only causal loops allowed are what we might call ‘virtuous loops’—those that work out right.

What makes this confusing is that we’re used to analyzing causality by looking at the conditions preceding the effect. Here, we don’t see the ‘virtuous loop’ conditions being set at any particular point in time. The conditions have to apply to the continuum as a whole—from outside it, in effect.

You Can’t Avenge the Future

When Tony initially declares Scott’s proposed “time heist” impossible, the remaining Avengers bring in Bruce Banner as a substitute scientific resource. Banner (who now combines his own brain with the Hulk’s body) does make a nod to the fact that his scientific expertise is primarily in biology, not physics, but the story remains basically true to the comic-book idea that a scientific genius is a genius in every science. At about 0:59, Banner says something that sounds rather like the Novikov principle we’ve been discussing: if you kill someone in the past, that doesn’t erase their later selves. Apparently causality doesn’t propagate down the world lines of already-existing characters to wipe them out when their original causes go away. On this theory, Marty wouldn’t have had to worry about disappearing even if he couldn’t get his parents back together.

On the other hand, Bruce doesn’t seem to be saying you can’t kill the person in the past; he seems to be saying that if you did kill them, it wouldn’t make any difference. This may have more to do with what TV Tropes calls “ontological inertia” (see here, but also here). Bruce’s approach seems to allow for wild inconsistency in the timeline, because I can be alive in 2019 even after being killed in 1971.

The simplest answer may be to conclude that Bruce wasn’t a very good physicist; maybe Tony silently corrected Bruce’s theory when Tony finally did agree to join the party.

Branching Timelines

At some point in SF history, people realized that the whole paradox thing could be avoided by introducing a third theory, the notion of multiple branching timelines. Niven’s phrase is “multiple time tracks.” If you change the past, the original future going forward from that point remains unchanged, but a new future comes into existence, branching off to take into account the change. (The character making the change always seem to end up in the new branch, not the old.) We can have our cake and eat it too: one version of me devours the cake, but another, equally real, version of me prudently saves the cake for later.

The multiple-timeline approach gains some headway from the general popularity of alternate-history stories, and some plausibility from the fact that physicists take seriously the suggested “many-worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics. It appears to solve the problem of time paradoxes. However, it runs very close to an assumption that would make it impossible to tell a good story at all.

Stories are about action and choice. A mere recounting of a series of experiences that happen to someone wouldn’t be much of a story (which is one reason the ending of 2001: A Space Odyssey is so weak). James Michener’s introduction to the novel Hawaii (1959), which describes the geological formation of the islands, is only part of a story because it lays the groundwork for what the characters later say and do.

If every possible alternative branched off a new timeline whenever there were options, there would be no point in making a choice, because whichever choice I made, another version of me would make the opposite choice. Niven captures the problem exactly:

If every possible alternative branched off a new timeline whenever there were options, there would be no point in making a choice, because whichever choice I made, another version of me would make the opposite choice. Niven captures the problem exactly:

. . . did you ever sweat over a decision? Think about one that really gave you trouble, because you knew that what you did would affect you for the rest of your life. Now imagine that for every way you could have jumped, one of you in one universe did jump that way.

Now don’t you feel silly? Sweating over something so trivial, when you were going to take all the choices anyway. And if you think that’s silly, consider that one of you still can’t decide . . . (p. 117)

The title story in All the Myriad Ways explores exactly that issue—what would happen if people really started to believe that all alternatives were equally real.

But suppose we assume that every choice doesn’t spawn alternate universes—just the changes caused by time travel, by backward causality. That doesn’t destroy all narrative in the way just described. It just ruins the story you’re trying to tell. The main characters move heaven and earth to get into the past and make the necessary change. They succeed! Whew. Victory. —Except that in another universe, the original one, they didn’t succeed. Somewhere, the sad failures who are Marty McFly’s parents still languish by the TV. That’s not a really satisfying conclusion.

Alternating Avengers

The multiple-timeline approach certainly comes up in Endgame. What I can’t make out is whether it prevails in the end, or is averted.

At about 1:24 in the movie, Bruce Banner is having a tense conversation with the Ancient One (Dr. Strange’s mentor) about the plan to return the stones to their original places in time. The idea is that if he takes the Time Stone from the Ancient One at (let’s say) 1:03:12 p.m. on January 31, 2010, and eventually Steve Rogers returns it to her at 1:03:13 p.m. on January 31, 2010, there won’t be a need for a branch to form. History continues on as it had always been. (Steve describes his mission concisely at 2:43 in the movie: “I know. Clip all the branches.”) Thus, the timeline of the movie, in which Thanos Snapped half the universe away, and five years later the assembled Avengers brought them back and did away with Thanos, remains the one-and-only timeline. There’s a helpful description of this procedure in an article from July 2019 (which is also full of spoilers, by the way).

At about 1:24 in the movie, Bruce Banner is having a tense conversation with the Ancient One (Dr. Strange’s mentor) about the plan to return the stones to their original places in time. The idea is that if he takes the Time Stone from the Ancient One at (let’s say) 1:03:12 p.m. on January 31, 2010, and eventually Steve Rogers returns it to her at 1:03:13 p.m. on January 31, 2010, there won’t be a need for a branch to form. History continues on as it had always been. (Steve describes his mission concisely at 2:43 in the movie: “I know. Clip all the branches.”) Thus, the timeline of the movie, in which Thanos Snapped half the universe away, and five years later the assembled Avengers brought them back and did away with Thanos, remains the one-and-only timeline. There’s a helpful description of this procedure in an article from July 2019 (which is also full of spoilers, by the way).

If we leave aside how hard it would have been to put things back exactly as they were, given the butterfly effect—not all the Stone retrievals were as simple as Bruce’s—does this work? Did the screenwriters (Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely) come up with a way to manage the dizzying time loops and still save the story?

I’m still not quite sure. One glaring plot hole, as various people have pointed out, is that we have to account for Thanos himself. In order to give us a great battle at the end (and what a battle it is!), the movie has Thanos in pre-Snap 2014 discover what’s going to happen and time-travel forward to 2019, where he’s ultimately disintegrated by the Avengers. He never returns to 2014. That seems to mean that the disappearance of Thanos did create a branch, since if he vanished from 2014 and never came back, the Snap would never have occurred.

At least that reduces us to two timelines, the one we see in the movie and another where Thanos does not continue to exist after 2014. And, interestingly enough, the Avengers’ actions saved both of those timelines from the Snap. The people who lived through the movie timeline experienced the Snap, but the lost people were eventually returned. Meanwhile, in the new alternate timeline, Thanos never came back, he never got the Infinity Stones, and the Snap never occurred. That’s not such a bad (dual) ending.

I don’t know. All these causal loops produce a kind of shell game in which I’m not quite sure how things came out. Nonetheless, it’s a great movie, if you like the Marvel characters at all. If you haven’t seen it, you shouldn’t have been reading this (but maybe the circuitous account above will be helpful). If you have—see it again! Just don’t try to go back to April to catch the premiere a second time; who knows what that would do to the space-time continuum.

The stories that inspire us, and help form our attitudes, tend to undermine this recognition and subliminally support our reluctance to participate. A story is more dramatic if everything comes down to the actions of one, or a few, people. If James Bond doesn’t pull off this next stunt, the World Will Come To An End. Will Smith and Jeff Goldblum, alone, deliver the computer virus that takes down the mother ship in Independence Day, which conveniently disables all the rest; the entire tension of the plot is funneled through that one bottleneck, as it were. A few superheroes save the universe—well, half of it—in the Avengers movies. In Netflix’s just-released Enola Holmes movie (mild spoiler), the heroine’s actions save the one person who casts the deciding vote on a British reform act. We love this trope.

The stories that inspire us, and help form our attitudes, tend to undermine this recognition and subliminally support our reluctance to participate. A story is more dramatic if everything comes down to the actions of one, or a few, people. If James Bond doesn’t pull off this next stunt, the World Will Come To An End. Will Smith and Jeff Goldblum, alone, deliver the computer virus that takes down the mother ship in Independence Day, which conveniently disables all the rest; the entire tension of the plot is funneled through that one bottleneck, as it were. A few superheroes save the universe—well, half of it—in the Avengers movies. In Netflix’s just-released Enola Holmes movie (mild spoiler), the heroine’s actions save the one person who casts the deciding vote on a British reform act. We love this trope.![]() In the books, Denethor sensibly sends a messenger from Minas Tirith to Rohan to call for help. But the movies leave it to Gandalf and Pippin to fire up a beacon that transmits the call to Rohan. (The fact that the lighting of the beacons is one of the most terrific scenes in the whole series doesn’t entirely mitigate the plot diversion.) When the Corsair ships sailing up the Great River to Minas Tirith turn out to contain relief for the city rather than further invaders, the movie makes this just Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli, along with the faceless army of the Dead—rather than a whole array of human reinforcements from South Gondor, as in the books.

In the books, Denethor sensibly sends a messenger from Minas Tirith to Rohan to call for help. But the movies leave it to Gandalf and Pippin to fire up a beacon that transmits the call to Rohan. (The fact that the lighting of the beacons is one of the most terrific scenes in the whole series doesn’t entirely mitigate the plot diversion.) When the Corsair ships sailing up the Great River to Minas Tirith turn out to contain relief for the city rather than further invaders, the movie makes this just Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli, along with the faceless army of the Dead—rather than a whole array of human reinforcements from South Gondor, as in the books. Right here in Virginia, we had an election in 2017 that resulted in a literal tie: an equal number of votes for each candidate. A purely random action had to be used to break the tie. “Each candidate’s name was placed in a film canister; those were then placed into a bowl and one name was drawn.” (NPR, 1/4/2018)

Right here in Virginia, we had an election in 2017 that resulted in a literal tie: an equal number of votes for each candidate. A purely random action had to be used to break the tie. “Each candidate’s name was placed in a film canister; those were then placed into a bowl and one name was drawn.” (NPR, 1/4/2018) For my own locality in Virginia, here’s a guide to voting early, voting by mail, and voting on Election Day. The local paper has a Web site on How to Vote, by state; I haven’t researched that reference in detail, but it may be useful. Here are three articles on drop boxes for ballots.

For my own locality in Virginia, here’s a guide to voting early, voting by mail, and voting on Election Day. The local paper has a Web site on How to Vote, by state; I haven’t researched that reference in detail, but it may be useful. Here are three articles on drop boxes for ballots.