At the end of the previous post, we noted that, depending on the kind of story authors want to tell, they may choose to deploy either a professional hero—someone whose job it is to face perils and challenges, like a military officer or police officer—or, on the other hand, someone who is dragged unwillingly or unexpectedly into a crisis. But I didn’t actually say much about how that difference plays out in a story. This post, then, is a kind of afterthought to the last one.

“You Are Not Prepared”

The first expansion for the online game World of Warcraft greeted players with the ominous declaration, “You Are Not Prepared.” That’s exactly the situation of the individual who didn’t expect to be called upon to be a hero. The lack of preparation may manifest itself in several ways, any of which can help to shape the story.

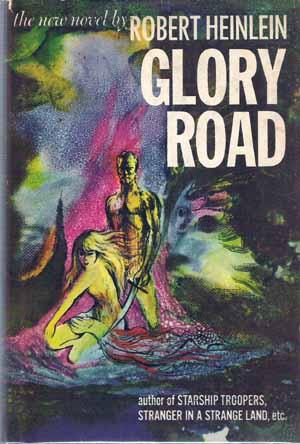

Competence. The main character (MC) may lack the skills or expertise to deal with the kind of crisis that’s occurring. Maybe there’s fighting involved, and the MC isn’t skilled with fists or swords or rayguns or whatever the weapon of choice happens to be. It’s a lot easier if they do happen to have the pre-existing skill: Glory Road’s Oscar, for example, was already experienced at fencing. If they don’t, then one can expect an extended period of training, since this sort of skill isn’t one that can be picked up in a day. Luke’s training montage in The Empire Strikes Back is a classic example, taking him from someone with potential and the occasional burst of unexpected powers (“Use the Force, Luke”) to someone who can face off against Darth Vader at the end of Empire and present himself as a full-fledged Jedi Knight at the beginning of the sequel.

Information. The amateur hero may be drawn into an environment where they aren’t familiar with the geography, the factions, the customs, the people and powers. In Anne McCaffrey’s Restoree, for example, the heroine is kidnapped by aliens, then rescued by others, all in an unconscious state, and “comes out of it” to find herself in a thoroughly incomprehensible situation. Glory Road reflects the same struggle by a MC to cope with an unfamiliar environment, though in this case the hero has all the assistance one could desire in learning to deal with the new circumstances.

The same kind of thing occurs in the classic fantasy trope where MCs from a backwater locale are sent into a wider world with which they’re only vaguely acquainted, as in The Lord of the Rings or The Wheel of Time. One of the advantages of this setup is that the MCs will need to have many things explained to them by more knowledgeable characters; they are the “ignorant interlocutors” whose presence is so convenient for exposition.

Even in more mundane cases, the MC may be placed in conditions where they don’t know their way around. The eponymous TV series hero Chuck Bartowski is suddenly pitched into the world of intelligence operations and secret agents; he and other characters spend much of the first three seasons learning the ropes. In a similar way, but much faster (in a two-hour movie rather than a long-running series), the hero of Hitchcock’s North by Northwest must learn the players and the goals of the spy game into which he has been drawn.

Confidence and maturity. The MC may also be personally unprepared to deal with the crisis posed by the plot. My favorite example is Romancing the Stone, in which the shy, introverted heroine suddenly has to travel far from home, ally with an unexpected stranger, fight her way through a jungle, and match wits with smugglers and thugs. Much of the fun of the story is in watching the ironically-named Joan Wilder gain in courage and self-reliance as she overcomes these progressively more dramatic challenges.

Other aspects. The MC may be unprepared in other respects. The elemental fact of facing death will be a shock to those of us brought up in more placid situations. The hero may lack equipment or resources to deal with the new challenges—or, conversely, may happen to have exactly the right resources available; this may actually bring about the adventure, as with the spacesuit in Heinlein’s Have Spacesuit, Will Travel. Moreover, the homebody hero probably has not yet come to terms with the degree to which the adventure might impact family or personal connections—unlike the hero-by-trade, who has probably reconciled spouse or family with a dangerous career.

The Character Arc

The need to cope with such challenges almost automatically sets up an arc of character development for the MC, reflected in the examples above. The MC can be expected to grow in confidence and independence. They may also be tempered by tragedy or suffering; this is the primary course for the young graduate-school characters in Gay Gavriel Kay’s Fionavar Tapestry.

The developing hero may become more street-savvy, more knowledgeable in the ways of the world. This sort of practical wisdom is a common theme, given the age of the characters, in young adult-targeted stories or the bildungsroman. For example, Rod Taylor, the MC of Heinlein’s young adult novel Tunnel in the Sky, becomes the informal leader of a band of marooned students by a gradual process. A group of older students, schooled in political theory and more alert to how groups can be manipulated, ease him out and take over control—with the best of intentions, to be sure. By the end of the story Rod, once again in command, has become a bit more canny in dealing with the group. In a similar way, Don Harvey in Between Planets starts out as a fairly naïve high-schooler who learns some hard lessons about political realities as he becomes embroiled in an interplanetary revolution.

Finally, if the MC learns new skills or abilities in the course of the story, they will have grown in that respect too. The new abilities may qualify the MC for new roles or positions, and perhaps to actually become a professional hero in the end. We see this in superhero origin stories, where a MC is initially unskilled in managing their superpowers, but gradually takes on the role of a professional do-gooder. Spider-Man is the classic example, a teenager who didn’t expect to become super-powered and takes a while to become used to his new potential; unlike, say, Iron Man or the Fantastic Four, who start out as grownups and adapt fairly quickly.

As we saw in the last post, an amateur hero almost by definition rises to the occasion. This is a sufficiently satisfying theme that I suspect adventure stories may tend more to this approach than to that of the professional hero—though I haven’t attempted to take a count.