Indiana Jones Rides Again

My wife and I went to see Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023) Friday night. Good movie—I’m unsure whether to call it “great.” My reaction was somewhat complicated by the fact that I’d inadvertently gotten us tickets to a theatre with the full range of tactile or “haptic” special effects—seats that bounce you around violently, drafts and puffs of air, sprinkles of water, little gizmos that tickle your neck or ankles. We both found all this paraphernalia rather distracting at first, though it’s undeniably immersive—rather like seeing a movie and riding a thrill ride at the same time.

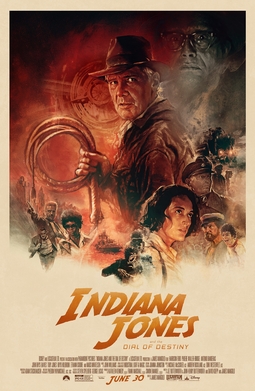

I’m going to try and avoid spoilers on this occasion, since it’s likely a lot of us haven’t seen this episode yet. (It’s fun to get in on opening night sometimes—and I have to keep up my geek cred somehow.) This closing episode—Harrison Ford and the Spielberg/Lucas team have all said this is to be Indy’s last outing, though I wouldn’t be surprised to see further spinoffs, like the The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles—provides a useful opportunity to reflect on the series as a whole, which we can do without major spoilers.

What Makes Indy Go

Part of what makes the Indiana Jones films so much fun is their unabashed appeal to action-packed derring-do—the meat and drink of the old-time movie serials that both Lucas and Spielberg have pointed to as inspiration. In that respect, it’s close kin to Star Wars—no surprise, since Lucas was behind that series as well.

Another key element is the character of Indy himself. He performs incredible (perhaps impossible) physical feats, but he always seems to be doing it in desperate improvisation—no Superman he. And while he’s an honorable cuss with a warm heart, there’s also a vein of pragmatism that makes him earthier than a traditional noble hero. (Remember the scene in Raiders where, finding Marion tied up in Belloq’s tent, he has second thoughts while untying her and, to her outrage, ties her back up again?)

The plot driver in each film is a lost and significant object: the Ark, a jewel, the Grail, the Crystal Skull, the Antikythera mechanism. The child in us can’t help responding to the appeal of “buried treasure.” From the children’s adventures of Nancy Drew or of Enid Blyton’s numerous literary offspring, to the (slightly) more grown-up exploits of National Treasure or Pirates of the Caribbean, we’re fascinated by the idea of suddenly discovering some hidden thing of inestimable value. Even a contemporary middle-grade book like Morgan Matson’s The Firefly Summer can invoke the same perennial attraction. Of course, “old” is relative—it might be as recent as one’s parents’ generation, or as far back as prehistory. The antiquities in at least three of these movies are thousands of years old, which is plenty far enough to evoke awe and wonder.

In the best of the IJ movies, this sense of wonder is intensified and elevated by the fascination of the numinous: a religious or near-religious awe. By the “best” movies I mean, of course, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, which I believe are generally regarded as the best of the bunch. I don’t think Dial of Destiny will rise to that level, though it’s certainly far better than the weakest link, Temple of Doom. (Of course, your mileage may vary . . .) The old-time movie-serial ambiance seems better suited to the power of myth than to the science-fiction veneer of the final two episodes.

The Tomb Raider Syndrome

I gather Indy has inspired a number of young people to become actual archaeologists. That’s a good thing, although as soon as we invoke actual archaeology, we have to acknowledge how far Indy wanders from scientific best practices. I must admit I cringe a little every time Jones and a companion shove a stone cover violently off a tomb, presumably to crack and shatter on the floor out of camera range—not to mention the absence of any attempt even by 1930s standards to photograph or otherwise record these unique historic sites. Last Crusade even highlights the difference between real archaeology and mere treasure-hunting: Indy tells his class “. . . and X never, ever marks the spot”—which caution is then promptly spoofed when he discovers that a giant X (the Roman numeral ten) actually does indicate where a catacomb is buried in Venice.

Of course, Indy has bigger fish to fry, so we blink amiably at these scientific solecisms and get on with the nonstop excitement. The cavalier treatment of relics is a long-standing tradition, shared (I think) by Indy’s distaff counterpart Lara Croft, among others. In our more pedantic moments, we may raise our eyebrows at these dubious tactics, but this is a case where TV Tropes’ “MST3K Mantra” applies: “It’s just a show; I should really just relax.” Indy himself does aim to do the right thing by history: he’s constantly contrasted with more mercenary grave-robbers when he insists, “This should be in a museum.”

The Human Element

More important, though, in Indy’s appeal to an eager audience is the human connections. They’re less prominent than the thrills and special effects, but they’re at the heart of the stories. Indy’s romance with Marion and his friendship with Sallah, and even his rivalry with the elegant Belloq, give us an enjoyment that outlasts the fight or chase scenes.

Lucas and Spielberg doubled down on this in Last Crusade, where Indy’s relationship with his father made for most of the more memorable moments of that film. On the other hand, serious human relationships are largely absent from Temple of Doom, whose single saving grace (aside from the mine-cart ride) is his friendship with Short Round. As an unregenerate romantic, I give Kingdom of the Crystal Skull extra points for reviving Indy’s romance with Marion (after his ephemeral affairs in the second and third installments).

In this respect, I think Dial may fall a bit short. While Indy’s relationship with his Action Girl goddaughter is a central theme in this movie, I didn’t find the new character quite as likable or interesting as I wanted to. There are some heartwarming moments here, to be sure, but they tend to bunch up toward the end of the story.

All in all, Dial gives us a distinctly quieter and more elegiac ending than the previous episode’s celebratory denouement. The lasting appeal of this film may have a lot to do with how audiences respond to the character arcs. After forty-two years, we can fondly say farewell to Indiana Jones in this concluding episode—though after all the thrills and chills, we may feel, with Indy, that “it’s not the years, it’s the mileage.”

> “we’re fascinated by the idea of suddenly discovering some hidden thing of inestimable value”

Humans seem to have evolved in feast-or-famine conditions. No wonder that we get crazy about the idea of a big score, even if it isn’t of mastodon meat anymore.

So nice to see a new entry!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point! But there seems to be something extra-fascinating about a *hidden* big score — possibly the unexpectedness, or the gratuitousness. Rather like a Christmas gift, maybe . . .

LikeLike

Pingback: The Professional Hero | Rick Ellrod's Observatory