Another rerun, adapted from a post from seven years ago.

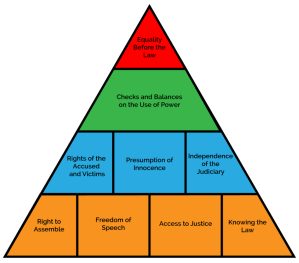

We’ve talked about how the Star Trek-Star Wars divide reflects preferences for a more lawful or more chaotic world; how F&SF stories often show us a defense of civilization against chaos; and how civilization makes science possible and rests in turn on human technology. But both order and technology can be oppressive. The missing element is the rule of law.

Universal Laws

It’s a crucial element of right governance that there are rules applying to everyone, as opposed to the arbitrary wishes of a dictator, who can make decisions based on favoritism, political preferences, or personal relationships. The Wikipedia article describes rule of law as “the legal principle that law should govern a nation, as opposed to being governed by decisions of individual government officials.”

As we saw in the recently updated post The Good King (reprise), the concept of the rule of law goes back at least to Aristotle. It became a central principle of the American founders via the English tradition of John Locke. “Rule of law implies that every citizen is subject to the law, including lawmakers themselves” (Wikipedia again). It is thus in tension with kingship, where rule is almost by definition arbitrary and personal. But one can have mixed cases—kings who are bound by certain laws, as in the British constitutional monarchy.

Without the rule of law, we depend on the good behavior of those who have power of some sort—physical, military, economic. We slide toward the “war of each against all,” where might makes right and the vulnerable are the pawns of the strong. Autocracy soon follows, as people look for any means to find safety from those who are powerful but unscrupulous. Hence the quotation from John Christian Falkenberg, which I’ve used before: “The rule of law is the essence of freedom.” (Jerry Pournelle, Prince of Mercenaries (New York: Baen 1989), ch. 21, p. 254.) Strength itself, a good thing, is only safe under laws.

Test Cases

It’s easy to miss the importance of the rule of law. We’re typically born into a society with better or worse laws, and criticize them from the inside. It’s less common to find ourselves in straits where lawfulness as such has collapsed. Regrettably, sizable numbers of people are exposed to such conditions in the world today. But many of us are fortunate enough not to see them ourselves. As always, fantasy and science fiction provide useful “virtual laboratories” for examining the possibilities.

A classic SF case is where a group thrown into a “state of nature” attempts to set up a lawful society. For example, in Heinlein’s Tunnel in the Sky (1955), students from a high-school class on survival techniques are given a final exam in which they are dropped onto an unspecified planet to survive for up to ten days. When an astronomical accident leaves them stranded, they need to organize for the long term. Rod Walker, the hero, becomes the leader-by-default of a growing group of young people. The tension between this informal leadership and the question of forming an actual constitution—complete with committees, regulations, and power politics—makes up a central theme of the story.

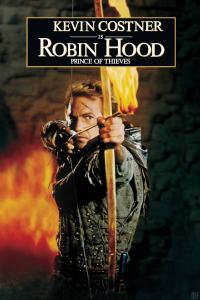

David Brin’s post-apocalyptic novel The Postman (1985), later made into a 1997 movie with Kevin Costner, illustrates the power of civil order, the unstated practices of a culture, as recalling—and perhaps fostering—the rule of law. The hero, a wanderer who happens to have appropriated a dead postman’s uniform and mail sack, presents himself as a mail carrier for the “Restored United States of America” to gain shelter in one of the isolated fortress-towns, ruled by petty tyrants, that remain. His desperate imposture snowballs into a spreading movement in which people begin to believe in this fiction, and this belief puts them on the road toward rebuilding civilization. The result is a sort of field-test not only of civil order and government, but of what Plato famously imagined as the “noble lie.”

In Niven & Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer (1977), a small community headed by a United States Senator hopes to serve as a nucleus for reconstructing civilization after a comet strike. We see at the end the strong pull of personal rule or kingship: as the Senator lies dying, the future of the community will be determined by which of the competing characters gains the personal trust and endorsement of the people—and the hand of the Senator’s daughter, a situation in which she herself recognizes the resurfacing of an atavistic criterion for rule. Unstated, but perhaps implicit, is the nebulous idea that deciding in favor of scientific progress may also mean an eventual movement back toward an ideal of rule by laws, not by inherited power.

Seeking a Balance

The “laboratory” of F&SF is full of subversions, variations, and elaborations on the rule of law. In particular, we should note the counter-trend previously discussed as “chaotic good.” Laws can be stifling as well as liberating.

Heinlein’s The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress (1966) imagines how the “rational anarchy” of a lunar prison colony is mobilized to throw off autocratic rule. The healthy chaos of the libertarian Loonies is hardly utopian, but the story does make it seem appealing. Interestingly, Heinlein returned to this setting with a kind of critique twenty years later in The Cat Who Walks Through Walls (1985), where the post-revolution lunar anarchy seems much less benign, seen from an outsider’s perspective.

While fantasy seems to concern itself with this issue much less than science fiction, consider the region called the “Free Commots” in Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain. When protagonist Taran visits this area in the fourth book (Taran Wanderer), he finds a society of independent villages, where the most prominent citizens are master-craftspeople. They neither have nor need a lord to organize them. The Commots contrast favorably to the feudal or wilderness regions through which Taran travels. A kind of anarchic democracy, as an ideal, thus sneaks into what otherwise seems to be a traditional aristocratic high fantasy.

One way of managing the tension between a government of laws and a culture of liberty is the principle of subsidiarity: the notion that matters should be governed or controlled at the lowest possible organizational level where they can be properly handled. It’s frequently illustrated in G.K. Chesterton’s ardent defenses of localism. In The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904), extreme localism is played for laughs—“half fun and full earnest,” to borrow Andrew Greeley’s phrase. The more mature Tales of the Long Bow (1924), which might qualify as a sort of proto-steampunk story, treats the idea more seriously, in the form of an oddly high-tech (for 1924) revolt of local liberty against overweening and arbitrary national rule.

It remains true that we need good people as well as sound laws. “Good men can make poor laws workable; poor men will wreak havoc with good laws” (James M. Landis, 1960; see this article at 432 & n.107). The quality of a civilization can also be assessed by whether it fosters citizens who act with decency and good judgment even when there isn’t a law to constrain them (as in David Brin’s “Ritual of the Street Corner”). After all, we neither can nor should try to create laws to govern everything.

But being willing to improvise well in situations where no law applies is different from considering oneself above the law, disdaining the constraints that apply to everybody else. This is doubly and triply true of rulers, who are constantly tempted to arrogate power and dodge accountability to accomplish their ends. If a ruler is allowed to get away with law-breaking, we’re headed for trouble.

Brin has noted that the stories that fill and shape our culture—movies, books, television—encourage a broad “suspicion of authority” that tells us all institutions are corrupt or useless, and so are most other people—so that the heroes and heroines of the stories can face and overcome challenges by their heroic actions. Like most attitudes, suspicion of authority is helpful in moderation, but corrosive when it gets out of hand. If that attitude leads us to throw over laws and institutions altogether in the hope that individual heroes or autocrats will save us, we need to keep in mind that benevolent dictatorship, unconstrained by law, is just one step away from despotism.

The Fragility of Civilization

When we grow up taking for granted the rule of law, we can fail to see how vulnerable it is—along with the civilization that it reflects and makes possible.

“The Establishment,” as they used to say in the 1960s, seems vast and invulnerable. When we’re trying to make a change, it seems insuperable, so rigid that nothing can be done about it. But this is an illusion. The structure of civilization, good and bad, is fragile. It’s easier than we think to throw away the rule of law, so painfully constructed (as Rod Walker found), in favor of shortcuts or easy answers to our problems.

One thing F&SF have brought us is a better sense of this vulnerability. The spate of post-apocalyptic tales in recent years—zombie apocalypses, worldwide disasters, future dystopias like The Hunger Games, going all the way back to the nuclear-war stories of the 1950s—do help us appreciate that our civilization can go away.

But that collapse doesn’t require a disaster. Civilization, and the rule of law, can erode gradually, insidiously, as in the “Long Night” stories we’ve talked about earlier.

Historically, the Sixties counterculture fostered anarchists who felt “the Establishment” was invulnerable. Often with the best of intentions, they did more to undermine civil order than they expected. Those who now see no better aim than breaking up the structures of democratic government and civil life—whether from the side of government, or from the grass roots—also fray the fabric of civilization. The extrapolations of science fiction and fantasy illustrate why eroding the rule of law should not be taken lightly.

Near the bottom of Brin’s Web home page, he places the following:

I am a member of a civilization

It’s good that we have a rambunctious society, filled with opinionated individualists. Serenity is nice, but serenity alone never brought progress. Hermits don’t solve problems. The adversarial process helps us to improve as individuals and as a culture. Criticism is the only known antidote to error — elites shunned it and spread ruin across history. We do each other a favor (though not always appreciated) by helping find each others’ mistakes.

And yet — we’d all be happier, better off and more resilient if each of us were to now and then say:

“I am a member of a civilization.” (IAAMOAC)

Step back from anger. Study how awful our ancestors had it, yet they struggled to get you here. Repay them by appreciating the civilization you inherited.

It’s incumbent on all of us to cherish and defend the rule of law. Give up civilization lightly, and we may not have the choice again.