Two Ways to Meet

In The Holiday, Kate Winslet’s character Iris comes upon an old man who’s hobbling about his own neighborhood, having forgotten where his house is. (He’s a once-famous movie screenwriter, but she doesn’t know that yet.) When she takes him home, he remarks, “Well, this was some meet-cute.” And, having lampshaded the trope by name, he introduces Iris to one of the classic conventions of romantic comedy: the main characters’ first meeting is awkward, confusing, adorable, or just plain cute.

On the other hand, the romantic couple in adventure stories is often thrown together by the adventure itself. The meeting is not so much cute as conflict-driven: let’s call it a “meet-hard.” The two types of encounters are both unusual—not your average first date—and, though they are opposites in some sense, they have some features in common.

Bumping Into Each Other

The simplest case for the meet-cute, as TV Tropes notes, is for the characters literally to crash into each other by accident—coming around a corner, for instance. This gives us physical contact, the resulting embarrassment, and a way to get the characters interacting at once.

In Notting Hill (1999), Hugh Grant’s bookstore owner chats briefly with Julia Roberts’ movie star when she browses around his bookshop. But he kicks off the relationship when he later collides with her outside and (naturally) spills his drink on her, necessitating a costume change. In the Good Old Summertime, the musical version of the “Shop Around the Corner” story (1949), also has the main characters meet in a collision, causing them to take an instant dislike to each other (a sure sign of impending romance in a rom-com). The embarrassment factor is amplified by the fact that he then accidentally shreds her skirt.

In Notting Hill (1999), Hugh Grant’s bookstore owner chats briefly with Julia Roberts’ movie star when she browses around his bookshop. But he kicks off the relationship when he later collides with her outside and (naturally) spills his drink on her, necessitating a costume change. In the Good Old Summertime, the musical version of the “Shop Around the Corner” story (1949), also has the main characters meet in a collision, causing them to take an instant dislike to each other (a sure sign of impending romance in a rom-com). The embarrassment factor is amplified by the fact that he then accidentally shreds her skirt.

But of course a couple can also “bump into” each other less literally. For my money, the most adorable meet ever may be in the Hollies’ 1966 song “Bus Stop” (hear it here). The singer offers to share his umbrella with a cute girl at the bus stop. They then continue using the umbrella throughout the summer, rain or shine, as a kind of running joke, not to mention a pretext for standing close together. I’d love to see this played out onscreen. P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It To Psmith (1923) has another umbrella scene, but even sillier: Psmith sees an attractive girl stranded by the rain and, in classic insouciant Psmith manner, steals someone else’s umbrella to offer her gallantly.

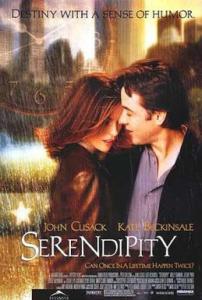

The recent Netflix rom-com Set It Up (2018) has the main characters deliberately arranging a meet-cute in an elevator as part of a plot to get their bosses to fall for each other. (It fails spectacularly.) In Serendipity (2001), one of my holiday-season favorites, the pair meet fighting over the last pair of black cashmere gloves at a department store.

The recent Netflix rom-com Set It Up (2018) has the main characters deliberately arranging a meet-cute in an elevator as part of a plot to get their bosses to fall for each other. (It fails spectacularly.) In Serendipity (2001), one of my holiday-season favorites, the pair meet fighting over the last pair of black cashmere gloves at a department store.

From the Ridiculous to the Sublime (And Back Again)

Resisting the temptation to highlight innumerable other favorite examples, I’ll point out some more exotic cases. The earnest trash-compactor robot in WALL-E (2008) meets the girl robot of his dreams, EVE, when she is dropped nearby to scout the long-defunct Earth for plant growth. He spends the next several sequences frantically dodging the suspicious droid’s laser blasts, before they get more comfortable with each other. Once EVE finds a sample and goes inert, we even see WALL-E gallantly shielding her from the rain with an ancient bumbershoot. There’s just something about umbrellas; most likely it’s that they represent a very mild way of depicting a damsel in distress.

In the best of Heinlein’s juveniles, Have Spacesuit—Will Travel (1958), high-schooler Clifford Russell is trying out a working spacesuit he’s won in a contest when he gets a distress call from someone who’s escaped from hostile aliens in their flying saucer. When he’s captured himself, he meets the caller, Peewee, a genius-level eleven-year-old. Given the characters’ respective ages, there is no actual romance in the usual sense, though they become fast friends—and there’s no question but that they’ll fall for each other when they get old enough. I’d classify this as a meet-cute on an intergalactic scale.

Vehicular breakdown is almost as good a way as umbrellas to create unexpected pairings. In Georgete Heyer’s Arabella (1949), the eponymous Arabella’s carriage breaks down near the country “hunting box” of the (formerly) jaded Robert Beaumaris. A recent romance in Wild Rose Press’s Deerbourne Inn series, Amber Daulton’s Lyrical Embrace (2019), has Erica Timberly’s car break down, in the rain, no less, occasioning her rescue by her rock-group idol, Dylan Haynes. (Unaccountably, he doesn’t offer an umbrella.) Angela Quarles’ steampunk romance Steam Me Up, Rawley (2015) drops the hero into the heroine’s lap in a malfunctioning balloon, this being steampunk.

Vehicular breakdown is almost as good a way as umbrellas to create unexpected pairings. In Georgete Heyer’s Arabella (1949), the eponymous Arabella’s carriage breaks down near the country “hunting box” of the (formerly) jaded Robert Beaumaris. A recent romance in Wild Rose Press’s Deerbourne Inn series, Amber Daulton’s Lyrical Embrace (2019), has Erica Timberly’s car break down, in the rain, no less, occasioning her rescue by her rock-group idol, Dylan Haynes. (Unaccountably, he doesn’t offer an umbrella.) Angela Quarles’ steampunk romance Steam Me Up, Rawley (2015) drops the hero into the heroine’s lap in a malfunctioning balloon, this being steampunk.

The Meeting of Adventure

By the time we get to carriage or automobile mishaps (not to mention flying saucers), we’re edging into the territory of the adventure romance. (Which may be where I should have classified Have Spacesuit, except that the incident, the setting, and the characters are just so darn cute.) The “meet-hard” in an adventure story puts romantic interests together in exigent circumstances, defining their initial relationship in a different way.

There’s an entire subgenre of adventure romance stories. Goodreads lists (at this writing) 1,344 entries in the category “Popular Adventure Romance Books.” And that’s just the popular ones, apparently. However, that’s not precisely what I’m referring to here. In some cases—The Hunger Games is near the top of Goodreads’ list—the eventual lovers already know each other before the adventure begins. Here, I’m classifying an “adventure romance” as a romance in which the characters meet on or because of the adventure.

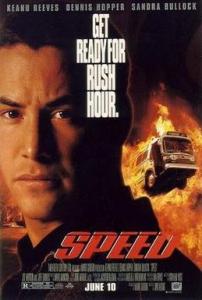

I think of the movie Speed (1994) as a classic example. Most of the action takes place on a bus equipped with a bomb that’ll go off if the bus’s speedometer drops below 50 miles per hour. Keanu Reeves’ character Jack Traven gets on the bus because he’s a police officer. His opposite number, Annie Porter (Sandra Bullock), is merely a passenger who ends up driving the bus. They bond over the course of the incident and are ready for a real date by the finale.

I think of the movie Speed (1994) as a classic example. Most of the action takes place on a bus equipped with a bomb that’ll go off if the bus’s speedometer drops below 50 miles per hour. Keanu Reeves’ character Jack Traven gets on the bus because he’s a police officer. His opposite number, Annie Porter (Sandra Bullock), is merely a passenger who ends up driving the bus. They bond over the course of the incident and are ready for a real date by the finale.

The adventure romance may shade over into a rescue romance, in which one character saves the other from some unfortunate fate, minor or major. But this doesn’t have to be the case; it’s just as likely the protagonists will end up cooperating in achieving their goal, becoming what TV Tropes calls a “Battle Couple.”

A Precarious Bond

Speed neatly illustrates (and lampshades) the great strength of the adventure romance: the stress and camaraderie of the adventure brings the couple together as “Fire-Forged Friends.” I’m especially fond of this trope (see The World Around the Corner and Rescue Redux). At the end of Speed, Jack tells Annie he’s heard that relationships “based on intense experiences” don’t work out, although they go ahead anyway. Interestingly, the sequel bears that out; Annie has a new boyfriend—though that seems to have been a function of actor issues (Reeves declined to appear).

A similar issue about the stability of adventure romances comes up in the sequel to National Treasure (2004), in which characters played by Nicholas Cage and Diane Kruger came together over a plot to steal the original Declaration of Independence. Their relationship has fallen apart by the time National Treasure 2 (1007) rolls around, but a new adventure gives them an opportunity to rekindle the spark.

A similar issue about the stability of adventure romances comes up in the sequel to National Treasure (2004), in which characters played by Nicholas Cage and Diane Kruger came together over a plot to steal the original Declaration of Independence. Their relationship has fallen apart by the time National Treasure 2 (1007) rolls around, but a new adventure gives them an opportunity to rekindle the spark.

Extraordinary Adventures

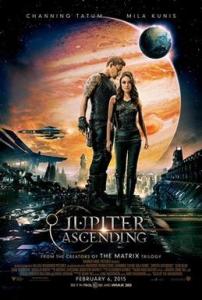

Since F&SF specializes in adventure, we see the meet-hard frequently in science fiction or fantasy works. In the first of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom books, A Princess of Mars (1912), John Carter meets Dejah Thoris when she is captured by the green Martians among whom Carter is living, and he becomes her defender.

The principal couple in E.E. Smith’s The Skylark of Space (first published 1928, revised book ed. 1946), Dick Seaton and Dorothy Vaneman, are already engaged when the story starts. However, when Dorothy is kidnapped and Dick sets out in pursuit accompanied by his fast friend, Martin Crane, it turns out that Dorothy has a lovely fellow captive, Margaret Spencer. Peggy and Martin form their own bond in the course of their epic space trip, and under these stressful conditions, it develops quickly enough that we get to see a double wedding on the planet Osnome.

The boy Shasta in The Horse and His Boy (1954), one of C.S. Lewis’s Narnian chronicles, meets an aristocratic Calormene girl, Aravis, on the road (ch. 2), and they share the adventures from then on. These characters are also too young for an actual romance, but Lewis dryly tells us at the end that “years later, when they were grown up they were so used to quarrelling and making it up again that they got married so as to go on doing it more conveniently.”

Another independent heroine, Eilonwy, has grown up living with a formidable witch, which is where Taran the young hero meets her in Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three (1964). She engineers Taran’s escape, which in only the start of five novels’ worth of achievements and escapades, with a marriage at the end (once they’ve grown up). Don’t even look at the Disney movie version of the story, but I do highly recommend Dawn Davidson’s graphic-novel adaptation, only partway through but very promising.

Another independent heroine, Eilonwy, has grown up living with a formidable witch, which is where Taran the young hero meets her in Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three (1964). She engineers Taran’s escape, which in only the start of five novels’ worth of achievements and escapades, with a marriage at the end (once they’ve grown up). Don’t even look at the Disney movie version of the story, but I do highly recommend Dawn Davidson’s graphic-novel adaptation, only partway through but very promising.

And, for an example that’s had a wider audience, in the Marvel movie Thor (2011) Jane Foster discovers the hero in the desert, where he’s just been dropped by an Einstein-Rosen wormhole. Their adventures continue through two movies, although by the third episode, lamentably, they seem to have broken up.

Only Slightly Extraordinary Adventures

Not all stories of adventure need to have fantastic elements—although by definition an adventure takes us out of ordinary, mundane life. The dangers and thrills of the real world are quite enough.

One of my favorite comedy-romance-adventures is the 1984 movie Romancing the Stone, in which romance novelist Joan Wilder ventures out of her quiet writer’s world to come to the aid of her sister, captured by smugglers in South America. The bus she’s riding in Colombia crashes into a jeep driven by an exotic-bird smuggler, Jack T. Colton. (I will leave to the reader the task of deciding whether this should count as a bump-into-each-other encounter, or a vehicular failure.) Jack and Joan end up as unlikely partners in a progressively (sorry, I can’t avoid it) wilder series of escapades that end in a romance—although this couple, too, will have to wait for a sequel to fully seal the deal.

One of my favorite comedy-romance-adventures is the 1984 movie Romancing the Stone, in which romance novelist Joan Wilder ventures out of her quiet writer’s world to come to the aid of her sister, captured by smugglers in South America. The bus she’s riding in Colombia crashes into a jeep driven by an exotic-bird smuggler, Jack T. Colton. (I will leave to the reader the task of deciding whether this should count as a bump-into-each-other encounter, or a vehicular failure.) Jack and Joan end up as unlikely partners in a progressively (sorry, I can’t avoid it) wilder series of escapades that end in a romance—although this couple, too, will have to wait for a sequel to fully seal the deal.

As noted above, there are lots of romance novels in this category as well. Many of them start with the mundane and develop complications as they go; for example, Jennifer Crusie & Bob Mayer’s Don’t Look Down (2006), which starts out filming a movie and ends up with (as Goodreads puts it) “trying to find out who’s taking ‘shooting a movie’ much too literally.”

There is a sort of degenerate form of the adventure romance (in the mathematical, not the moral, sense) in which characters that are thrown together in a thriller automatically pair up, whether there’s a reason for it or not. A writer can lean on the “forged in fire” trope without doing the work of showing how the characters are actually drawn together by the excitement. For example, I have on my shelf Gardner F. Fox’s The Hunter Out of Time (1965), which made an impression on me as a kid but which, in retrospect, I have to think of as a potboiler. When the time agent from the future who meets “adventurer” Kevin Cord turns out to be a beautiful girl, one is hardly surprised they end up falling for each other, basically because they’re there.

Some of these examples illustrate the gray area between the meet-cute and the meet-hard. Whether cuteness or crisis predominates depends on the context of the story. For example, the leads in The Wedding Planner (2001) meet when Mary (Jennifer Lopez) gets her high-heeled shoe stuck in a manhole cover and “Eddie” Edison pulls her out of the way of a speeding dumpster. It’s a genuine danger, but it doesn’t lead to a series of adventures; the overall setting is comic (as is the danger). On the other hand, the leads in Ready Player One (2011) meet in a gaming context, but their developing relationship is action-driven.

Some of these examples illustrate the gray area between the meet-cute and the meet-hard. Whether cuteness or crisis predominates depends on the context of the story. For example, the leads in The Wedding Planner (2001) meet when Mary (Jennifer Lopez) gets her high-heeled shoe stuck in a manhole cover and “Eddie” Edison pulls her out of the way of a speeding dumpster. It’s a genuine danger, but it doesn’t lead to a series of adventures; the overall setting is comic (as is the danger). On the other hand, the leads in Ready Player One (2011) meet in a gaming context, but their developing relationship is action-driven.

Where the Meets Meet

The meet-cute and the meet-hard share some features with respect to how they function in a story.

The style of the meeting can help set the tone for the story: comic, adventurous, or something else. This is true even in the mixed cases. Mary’s predicament in The Wedding Planner is slightly silly: she’s pinned down by getting her heel stuck, and the onrushing menace is not a Mack truck but a mundane dumpster. Similarly, Wade and Samantha in Ready Player One meet via action games; that tone is maintained when the action spills over into real life and real danger.

The style of the meeting can help set the tone for the story: comic, adventurous, or something else. This is true even in the mixed cases. Mary’s predicament in The Wedding Planner is slightly silly: she’s pinned down by getting her heel stuck, and the onrushing menace is not a Mack truck but a mundane dumpster. Similarly, Wade and Samantha in Ready Player One meet via action games; that tone is maintained when the action spills over into real life and real danger.

Both meet-cute and meet-hard have the effect of accelerating a relationship. They put the characters in contact with each other in a distinctive and memorable way. The quirkiness of the encounter, something the characters have in common, cuts short the process of “getting to know you” with which ordinary relationships begin. This is especially useful in movies, or short stories, where a limited time is available for a “slow burn” relationship to form. In that respect, these devices are similar to the love-at-first-sight convention (the “stroke of lightning”).

Finally, these non-ordinary meetings reveal something about the characters: how they deal with unusual situations. Are they self-conscious or self-confident? Do they come up with quick solutions to problems (whether or not involving umbrellas)? Do they know how to take action in a crisis? And, not least, do they have a sense of humor? The exceptional nature of the first meeting shows us more about the participants than we’d see if they simply met at work, say, or introduced themselves in a bar.

Either the meet-cute or the meet-hard, then, can kick off a romance with style—though very different types of romance may develop.