The Sign of the Sequel

Ever find yourself approaching the end of a new book—and you realize there’s no way the author can tie up the plot in what remains of the novel? It’s that moment when you realize: we’re in for a sequel.

That realization may be awful, or it may be exciting, depending on how much you enjoy the story so far. But it changes the way you look at the book you’re reading, to know it isn’t complete in itself, but only part of a larger tapestry. Your sense of the pacing and the shape of the story has to adjust.

But the story alone hasn’t told us there will be a sequel. Rather, we’re drawing on something outside the text itself—our knowledge of how much of the book remains—to tell us something about the story.

But the story alone hasn’t told us there will be a sequel. Rather, we’re drawing on something outside the text itself—our knowledge of how much of the book remains—to tell us something about the story.

Years ago, when I first read Isaac Asimov’s Second Foundation, I almost missed the last chapter altogether. The conclusion of the novel consists of a series of successive surprises, each overturning the last. The second-to-last chapter seemed to end so conclusively that I only turned the page because I was in the habit of reflectively turning over the blank endpapers of a book. —And there was the final chapter! I could only make that mistake, however, because the last chapter was so short—six pages in my hardcover edition.

It’s harder to make that kind of observation in an e-book, where there are no physical pages to observe. You can usually find a percentage or “location” indicator, but it’s not quite as obvious as the physical thickness of the pages.

Let’s call this process of drawing on outside information “meta-reading.”

Sources of Meta-Information

There are a number of sources from which we glean this meta-information, consciously or not.

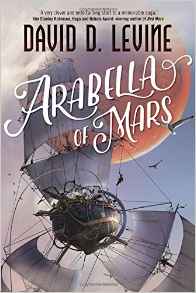

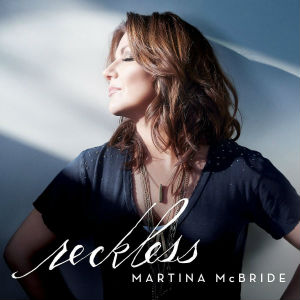

Starting from the broadest case, we get some information from the genre to which the book belongs. If you find a book in the science fiction section of the bookstore, then no matter how mundane the opening scenes may be, you can be pretty sure that something out of the ordinary is going to turn up at some point. If you’re reading a genre romance, you can rely on the ironclad rule that a genre romance must have a happy ending: either “happily ever after,” or at least “happily for now”—HEA or HFN, in the jargon of the trade. Even if the characters’ relationship seems doomed as you approach the ending, you can be pretty sure it’ll turn out well—which may not be the case in a “mainstream” novel.

Getting to know an author’s habits and preferences is another way to guess what’s going to happen in the end. If we’ve read a fair sampling of an author’s work, we can gauge fairly well the chances of a happy ending, the likelihood of violence or sex scenes, the kinds of characters you’re likely to meet up with. It’s a little more tense approaching the end of a book by a new author, because we’re not yet familiar with what kinds of tricks the writer may (or may not) be willing to pull at the denouement.

Then there’s the back-cover blurb, or the flyleaf—often the reason we pick up the book in the first place. The half-dozen paragraphs or so of teaser text on the flyleaf are designed to tell us just enough to get us interested. They shouldn’t give away the whole plot, but they do create expectations—which the book as a whole may or may not meet. Something that comes as a complete surprise to the characters may be something the reader is already primed for, because it’s part of the plot setup that the blurb describes.

Reviews take this principle further. A review may include spoilers, but even without actual spoilers, it tells is something even before we open page one.

Once we get into the book, there are still more clues. Chapter titles are out of fashion these days, but if there are such titles, they inevitably tell us something about what’s going to happen. In my current novel-in-progress, I use temporary chapter titles that remind me what happens in the chapter, but remain obscure enough not to telegraph the outcome to test readers. Still, when you reach the chapter titled “The Battle of Tremont,” you’re inevitably going to have an idea what to expect.

Finally, in the example I started with, the length of the book tells us something. As we move through the story, we can measure our sense of pacing with the literal progress through the pages. There have been a number of cases where it’s looked as if the plot was being wrapped up nicely, and I’ve looked at the mass of material still to come and thought, Something’s bound to come unglued here . . . or we wouldn’t have a hundred pages to go.

Setting Expectations

This kind of insight relies on an awareness of narrative practices. There are internal necessities to good storytelling. Guessing the imminence of the climax from the number of remaining pages, for example, depends on our assumptions about how much time after the climax will be devoted to wrapping things up—which, in a long story like The Lord of the Rings, can take quite a while.

Likewise, gauging the amount of space needed to resolve the plot assumes that the plot will be resolved: good authors, at least, don’t leave things totally dangling. Our use of meta-reading plays off our assumptions about how stories are told—and can go awry if the author’s views are radically different from the reader’s.

For that very reason, the writer of a story has to take into account the context in which the reader encounters the story, and the expectations raised in that context. The reader doesn’t come to the story as a blank slate.

If there will be major surprises in the tale, the writer (and publisher) need to make sure they aren’t given away in the blurbs. If the author wishes to undermine the expectations created by genre classification or advertising, it’s important to be aware of the consequences. Subverting reader expectations can be illuminating and satisfying to the reader, but it can also be annoying and frustrating. The implicit contract between writer and reader—‘I’m going to tell you a story you will enjoy’—places boundaries on just how subversive one can be without leaving the reader feeling cheated.

The writer’s conversation with the reader, then, extends well beyond the contents of the text itself. It’s something that’s useful to remember for the writer—and the reader as well.