The Convenient Newbie

It helps to have someone to explain things to—especially if you’re writing fantasy or science fiction.

How do we introduce our audience to the world where our story takes place? It’s something we have to think about even in a normal, contemporary setting. We have to give a sense of where our characters are and what they’re doing there, even if the answers are as mundane as “middle America” and “going to work on a Monday.” But this task is much more challenging if the setting is in the far future, or the distant past, or some entirely separate reality as in Game of Thrones. The same problem applies in some degree in a historical novel, or a tale set in a very different culture. How can we get readers or viewers acquainted with the milieu if much of it is unfamiliar?

Of course we can simply tell them about a setting directly: “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away . . .” But the audience won’t sit still for indefinite amounts of backstory before the main story gets going. On the other hand, another time-honored F&SF approach is just to throw the reader into the deep end and let them swim. But that makes for a steep learning curve, trying to absorb a lot of strange peoples and places and customs all at once. The throw-them-in approach may discourage readers or viewers not by boring them, but by making them scramble to keep up. Some will enjoy that challenge; but others may be daunted and close the book (or video).

One way to inform the audience is to make one of the lead characters an inexperienced person who doesn’t know much about their own world. Other characters will have to explain to this person things that they know perfectly well, but that this character is unfamiliar with. The “ignorant interlocutor” is a convenient stand-in for the reader, making the necessary exposition seem natural.

Some Convenient Examples

Hobbits might have been designed specifically for this role. The hobbits of the Shire are back-country unsophisticates, living quietly in a little country without much contact with the rest of the world. Once they’re taken out of their homely environment into the wider world, Gandalf or Aragorn or someone frequently has to explain things to them, helping the audience get acquainted with Tolkien’s vast world and history—or, at least, with those parts that are important to the story. (At the same time, we should note that Tolkien also uses other forms of exposition that no new writer could get away with nowadays. The Lord of the Rings actually opens with a sixteen-page Prologue providing background on such essential matters as pipe-weed—followed shortly in Chapter Two by fifteen pages of explanation in which Gandalf instructs Frodo on the challenge they face.)

Hobbits might have been designed specifically for this role. The hobbits of the Shire are back-country unsophisticates, living quietly in a little country without much contact with the rest of the world. Once they’re taken out of their homely environment into the wider world, Gandalf or Aragorn or someone frequently has to explain things to them, helping the audience get acquainted with Tolkien’s vast world and history—or, at least, with those parts that are important to the story. (At the same time, we should note that Tolkien also uses other forms of exposition that no new writer could get away with nowadays. The Lord of the Rings actually opens with a sixteen-page Prologue providing background on such essential matters as pipe-weed—followed shortly in Chapter Two by fifteen pages of explanation in which Gandalf instructs Frodo on the challenge they face.)

The most well-known SF parallel is Luke Skywalker, the unsophisticated farm boy who is catapulted into galactic affairs by the death of his foster parents and the charismatic advice of Obi-Wan Kenobi. When Obi-Wan tells Luke “You’ve taken your first step into a larger world,” he isn’t merely refering to the Force, but implicitly to Luke’s need to learn many things as he emerges from the backwater planet Tatooine.

The most well-known SF parallel is Luke Skywalker, the unsophisticated farm boy who is catapulted into galactic affairs by the death of his foster parents and the charismatic advice of Obi-Wan Kenobi. When Obi-Wan tells Luke “You’ve taken your first step into a larger world,” he isn’t merely refering to the Force, but implicitly to Luke’s need to learn many things as he emerges from the backwater planet Tatooine.

We don’t see quite such an inexperienced protagonist in the other trilogies, with Anakin or with Rey. By the time we see the prequel or the sequel trilogy, we’re already familiar with the Star Wars background, and not as much needs to be explained. Interestingly, Lucas too adds a more artificial form of exposition, the screen crawl at the opening of each film, perhaps primarily for its nostalgia value.

An Earthly culture of another time period can be just as unfamiliar as an extraterrestrial. Friday’s Child was the first Regency romance I read, and I found it a particularly good place to start. The naïve heroine, Hero Wantage, marries the kind-hearted but rakish Viscount of Sheringham and is carried off into the whirl of London society, whose manners and mores are often peculiar to modern eyes. We are introduced along with Hero to these rather arbitrary rules—if a carriage-race between females is high entertainment at a private country gathering, why is it a terrible social gaffe in public?—where her lack of understanding frequently lands her in a “scrape.” Similar inexperienced heroines also appear in other Heyer stories, such as Arabella and Cotillion (in descending order of ignorance or naïveté).

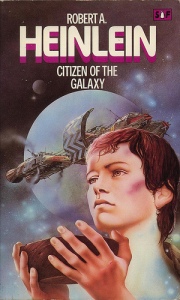

A science-fiction example of the socially inexperienced character can be found in Heinlein’s Citizen of the Galaxy. Thorby, the main character, must learn to copy with several unfamiliar environments in succession over the course of the story, but especially with the strict customs followed by the Free Traders, nomadic interstellar merchants. An anthropologist traveling with the Traders to study their culture is invaluable in explaining these customs to Thorby—and the reader.

A science-fiction example of the socially inexperienced character can be found in Heinlein’s Citizen of the Galaxy. Thorby, the main character, must learn to copy with several unfamiliar environments in succession over the course of the story, but especially with the strict customs followed by the Free Traders, nomadic interstellar merchants. An anthropologist traveling with the Traders to study their culture is invaluable in explaining these customs to Thorby—and the reader.

The ignorant interlocutor in Heinlein’s Beyond This Horizon, by contrast, is a minor character, “the Man from the Past,” who has been preserved from the present into the story’s centuries-later future by a time stasis field. He comes into the story only briefly, but long enough for Heinlein to get in some exposition about facets of the future society that are well-known to the other characters, but need to be explained to the archaic survivor.

A more well-known Heinlein story, Stranger in a Strange Land, uses space—and species—rather than time as the cultural differentiator. Michael Valentine Smith, the “Man from Mars,” is a human being raised from infancy by Martians. Many of the most interesting parts of the story show Mike trying to grapple with human customs when he arrives back on Earth as a young man—which also allows Heinlein to make satirical commentary on these peculiar creatures, the humans.

Some Storytelling Advantages

Having someone to explain things to is helpful because dialogue is often a better way to present information than authorial lecturing. A scene in which our puzzled naïf asks questions and gets answers—or makes mistakes and is corrected—is easier to make interesting. These interactions can accomplish other things at the same time. The way a conversation goes can reveal character and show relationships developing. It can be mixed with action—characters talk while they’re hiking, exploring a wrecked spaceship, dancing.

Making one character’s knowledge limited similarly allows us to avoid the dreaded “As you know, Bob” problem, in which characters tell each other things of which they are already well aware, to educate the reader at the expense of in-story plausibility. (The term comes from the Turkey City Lexicon, a guide to F&SF tropes for use in writing workshops.) TV Tropes has a particularly good discussion of this whole issue.

Where to Find Them

If we want to include an ignorant interlocutor in a story, what kinds of situations might naturally produce this sort of character?

Youth and inexperience tend to go together; and a curious child can serve the purpose (perhaps a precocious child, who is uninformed but capable of grasping the explanation once offered). TV Tropes’ term is “Little Jimmy.” But the explainee may also be a competent enough adult who has simply been thrust into a situation or milieu they’re not ready for. Cary Grant’s character Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest is a good example: he may be a fine advertising executive, but the world of international espionage is new to him. Captain Pausert of James Schmitz’s classic SF novel The Witches of Karres is an expert ship-handler and a pretty effective trader, but the young witches need to bring him up to speed quickly when he gets involved in Karres business.

Youth and inexperience tend to go together; and a curious child can serve the purpose (perhaps a precocious child, who is uninformed but capable of grasping the explanation once offered). TV Tropes’ term is “Little Jimmy.” But the explainee may also be a competent enough adult who has simply been thrust into a situation or milieu they’re not ready for. Cary Grant’s character Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest is a good example: he may be a fine advertising executive, but the world of international espionage is new to him. Captain Pausert of James Schmitz’s classic SF novel The Witches of Karres is an expert ship-handler and a pretty effective trader, but the young witches need to bring him up to speed quickly when he gets involved in Karres business.

The innocent naïf who needs to be told how the world works is another category, particularly if the story is going to deal with gritty realities. Several of our examples above count, and we might also mention yet another Heinlein character (he was fond of the trope), Max in Starman Jones, who’s described by Wikipedia as “a farm boy who wants to go to the stars” and learns the ropes from the cynical rogue Sam Anderson.

The uninformed party may also be the student of a new art—the beginner or newbie. Harry Potter is new to the wizarding world and has to have all kinds of things explained to him, including his own backstory. In Anne McCaffrey’s YA novel Dragonsong—one of the best of the Dragonriders of Pern books, in my opinion—it’s musicianship that young Menolly is learning as she’s suddenly brought into the Harper Hall’s training program. Captain Pausert’s induction into Karres witchery reflects some similar elements, in a very different situation—learning on the fly rather than in a structured environment. The character’s new situation may involve learning the art itself, or the folkways of the school, or both.

Finally, one of the functions of the sidekick can be as a foil to whom the principal character can explain things. Robin has played this role for Batman—at least in the wacky 1960s TV series. A classic case, of course, is Holmes and Watson; TV Tropes even dubs such an character The Watson (“the character whose job it is to ask the same questions the audience must be asking and let other characters explain what’s going on”). Master detectives, who are supposed to be smarter than the audience, form fertile ground for such relationships: Archie Goodwin, who is no dummy, regularly receives nuggets of wisdom from his immobile employer Nero Wolfe.

Finally, one of the functions of the sidekick can be as a foil to whom the principal character can explain things. Robin has played this role for Batman—at least in the wacky 1960s TV series. A classic case, of course, is Holmes and Watson; TV Tropes even dubs such an character The Watson (“the character whose job it is to ask the same questions the audience must be asking and let other characters explain what’s going on”). Master detectives, who are supposed to be smarter than the audience, form fertile ground for such relationships: Archie Goodwin, who is no dummy, regularly receives nuggets of wisdom from his immobile employer Nero Wolfe.

Finally, the person who graciously explains things is often a mentor figure—the wise or knowledgeable one, a Gandalf or an Obi-Wan, the polar opposite of the uninformed interlocutor. When the mentor’s job is primarily to educate the main character, this may explain why the mentor is around early in the story, but may disappear or become unavailable when the action starts to heat up.

Excellent post! And good point about what Tolkien could do then but not now (fiction keeps speeding up); no author today wants to be the one to put the dump in the info-dump.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post! I got right into it. Very good insights and observations – which are used in Margaret Atwoods sequel ‘The Testements’ which I am reading just now. Two young girls growing up inside and outside of Gilead need to learn and be told how it works on ‘the other side’, which helps the sequel flow well for both memory and for drama.

LikeLike

Good! You’re right — another helpful use of the person-who-needs-to-be-informed is to brush up the audience’s recollection of previous episodes.

LikeLike

Pingback: Portraying the Transhuman Character | Rick Ellrod's Locus

Pingback: The Amateur Hero | Rick Ellrod's Observatory