The Dutch House Poses a Question

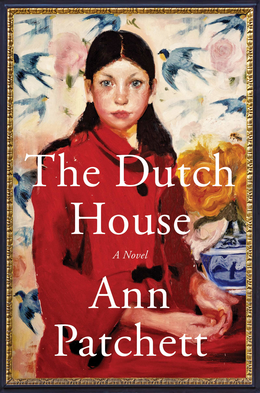

I now have a long commute two days a week—an hour minimum, more often 1¼ to 1½ hours—and this has given me an opportunity to start listening to audiobooks again. At my wife’s recommendation, I used the very useful Libby app to download a 2019 novel by Ann Patchett, The Dutch House. She had picked that one in part because the audiobook was read by Tom Hanks, who has a very agreeable voice.

It was an unusual pick for me. Much of my reading belongs to a few key genres: science fiction, fantasy, romance. The Dutch House belongs to that particular genre of contemporary writing that is often referred to as “mainstream” literature. While I don’t abhor mainstream fiction, it doesn’t often catch my attention.

I very much enjoyed this story, however. When you find yourself looking for an excuse to keep listening to the audiobook even once you get out of your car, that’s significant. The Dutch House made my commute considerably more enjoyable for the nine hours and 53 minutes it lasted. At the end, I felt that satisfaction and pleasure that comes when you’ve had a genuinely significant experience.

And that’s what poses the question. Because The Dutch House shares with much other mainstream fiction the characteristics that are sometimes referred to as “slice of life.” In particular, it doesn’t have much of a conclusion. The main characters meander along from childhood to about their mid-40s, and then the book stops. Plenty of interesting things happen along the way, the characters are well-drawn and fascinating, the scenes are vivid. But it doesn’t go anywhere.

Now, I generally prefer a story with a solid, clear climax and conclusion. So why did I enjoy this so much? Thinking about this led me to a bit of an epiphany about what’s appealing in fiction. While my own experience may be personal and idiosyncratic, my tastes are similar enough to lots of others’ that my ruminations may be of some more general applicability.

Since I need to point to a few specific things about Patchett’s story, I’ll issue a

Genre and Plot

In the non-mainstream genres I mentioned above, there tends to be a plot. There’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. The concerns of the characters come to a head at some point, and some kind of resolution is achieved. We can point to something that happened in the story, whether it is on the whole good, bad, or indifferent.

Now this is by no means universally true. Plenty of science fiction stories meander about without reaching a compelling conclusion. And there are some that do more to explore a mood than to tell a story. But there’s a tendency for the characters to get somewhere, whether or not it’s a place they wanted to be. And the types of SF that lack a conclusion are generally those that are deliberately trying to imitate mainstream fiction—to gain the greater cachet or respect accorded to Real Literature, for example.

This is even more true in other genres. A genre romance will have a happy ending, whether it’s “happily ever after” or merely “happy for now.” In a murder mystery, a killer is going to be unmasked at the end. Of course not every tale in real life ends this way; for one thing, people continue living after a given story has “ended.” But we can regard these genres as specializing in the subset of stories in which some portion of a person’s life can be marked off and form a satisfying tale that embodies a plot arc.

Plot and Achievement

Personally, I like a story in which something significant is achieved. It might be a really big thing: saving the world, bringing order to the galaxy, eliminating a Dark Lord. Or it might be something small and intimate: a love story, for example. It may be solely a matter of inner illumination, or, in certain kinds of tragedy, the demonstration of a tragic flaw. But the kind of plot we’re discussing is one that leads to a conclusion in which things are significantly different than they were at the beginning.

But theory must be shaped by experience. If my tentative generalization says I like a story only when something definite is achieved, then my enjoyment of a story that’s inconclusive is contrary evidence. In The Dutch House, while various characters realize and achieve certain things, there’s no overall resolution by the end. The several romances in the novel all fail. The main character, Danny, doesn’t really resolve his difficult relationships with his parents. No final judgment is suggested as to whether his mother, who left her children years ago to help the poor, is a saint or an irresponsible quitter. Many of the characters are likable and intriguing, but there isn’t precisely a hero or heroes. (A villain, perhaps, but since she’s subject to dementia and becomes an object of care in the latter part, there’s no viscerally satisfying comeuppance to be found.)

And yet, it’s a really good story. So what is it that I’m enjoying so much?

Significant Parts

I think it may be that the individual events in the story seem to matter, even if they don’t systematically lead anywhere. This is not the kind of mainstream novel in which people muddle around and leave the reader with a sense that it’s all been meaningless at the end. On the contrary: one feels that what these characters go through is important in some way.

It’s notoriously difficult to define exactly what “meaning,” in this sense, actually means. But whatever it is, the people and events in Patchett’s story have it. The good things that they do and experience serve to mitigate the bad things, and sometimes even make up for them. The events are presented as significant, even if they don’t rise to a marked climax.

Making the story meaningful in this way is a choice and an achievement, not a given. When there’s no clear plot arc in a story, it’s easy for the individual events to start seeming absurd. “Life’s a bitch and then you die.” But a good writer can ensure that meaning leaks through, as it were, throughout the story. There may be a hint of the same thought in an observation of Anne Lamott’s: “the purpose of most great writing seems to be to reveal in an ethical light who we are.” (Bird by Bird, Part Two, chapter 2, p. 104.)

So if my earlier thesis was that a good story is one in which something significant has been achieved, I need to modify it to include slice-of-life stories in which lives are shown to be meaningful.

(In)Conclusion

This essay itself is rather inconclusive. My ruminations on what makes for a good story are tentative and still incomplete. And I may merely be stating what’s obvious to readers who (so to speak) come from the opposite starting point: of course slice-of-life stories are meaningful, you bozo, what ever made you think otherwise? But it does seem to be an essential element in figuring out what makes for good storytelling.

Rick, great job of pointing out where one of these stories can go wrong, and how hard they can be to do right. Very interesting!!

LikeLike

I guess it’s best not to try and tie down too tightly what makes a good story. Any definition is going to throw up exceptions. In the end, I think a good story is simply one where the reader got something out of it, whether that’s a satisying conclusion, or simple enjoyment.

LikeLike

That’s fair, but to writers like Rick (and me too), “what makes a good story” is make or break for the amount of work we put in.

LikeLike

There are, to be sure, many kinds of things we can get out of a story, from pure entertainment and what Tolkien called “escape” to learning and moral formation. I do find it interesting in the abstract to ponder over what I find myself liking or disliking — and even more so when my preferences contrast with those of others (they liked THAT??! — How could they not admire THIS?!). Every now and then I learn to appreciate something new in the process. 😉

LikeLike