Too Many Books

Can one have too many books? I want to say no. (See the illustration, which hangs on our front hall next to the library.) On the other hand, it’s become difficult to fit my accumulated collection comfortably into any reasonable home—and doubly so when you add in my wife’s lifelong collection as well—even without the eight or ten boxes of books I sold off to the fabulous Wonder Books in Frederick in an attempt to thin out the collection. And nonfiction is another story. (Well, the stories are in the fiction section; but you see what I mean.)

This is so even though I’ve tried to exercise restraint by buying only those books I’ll want to read over again. I prefer to try out a new book by getting it from the library, and, after reading, to decide whether this is a “keeper” that I always want to have available. The rare exceptions are new books that I already know I’ll want to own, generally in a series. While Lois McMaster Bujold’s Vorkosigan saga was still coming out, for instance, I’d grab those off the bookstore shelves at once, sight unseen. (Though I admit I do have only an electronic copy of Gentleman Jole and the Red Queen—but that’s another discussion.)

Aside from considerations of space, it occurred to me some years ago that the “read again” rationale necessarily diminishes over time. Given my likely lifespan, how many times am I likely to reread any given volume? That number is constantly decreasing. This makes me a little cautious about buying new books—as opposed to using the library. One of the great perks of my current job is that there’s a county library branch right on the first floor of our building. I can put a book on hold and nip down while at the office to pick it up. Same thing to return it. A wonderful arrangement . . . at least until I retire . . .

The other motivation I’ve had for accumulating books has been a vague notion that they serve as a kind of reference library. In writing posts like these, it’s convenient to be able to grab a favorite book to check on some point or to make a citation precise. For years, I kept around an old paperback copy of Neil Jones’s The Planet of the Double Sun (1931, paperback edition 1967), merely as an example of a really crummy old-time SF yarn. It finally occurred to me that there was no particular purpose in having it—rereading it would be too boring to be worth any use I might make of the mention—and I ditched, er, released my copy to find a new home with some historian of SF. Haven’t missed it since.

The Great Reread

In the process of going over my packed-and-unpacked-and-reshelved books (two moves in the last two and a half years!), I’ve sometimes found it hard to recall what some of the stories were actually like. Or I feel as if I’d like to read a book once more before I consign it to the outermost depths. So I find myself rereading a lot of old material. Some of it holds up pretty well. Others, I wonder what I saw in the tale in the first place. The rereads end up being a combination of final trial—do I want to keep this book?—and fond farewell.

Of course I continue to read new stories too: new good books are coming out all the time. But it’s rather enjoyable to revisit some old friends as part of a balanced bookish diet.

And sometimes the old stuff may be worthy of comment. So I’m going to include the occasional post here from the Great Reread. The inspiration comes from Jo Walton’s brilliant series of essays, “What Makes This Book So Great,” originally hosted, I believe, at Tor and published in a 2014 collection. (There seems to be a list of links here; Walton’s own comments on rereading are here.) I’m not spotlighting what are necessarily the greatest books—but there may be interesting things to say even about the non-great or non-classic tomes I find cluttering my shelves.

Since these books tend to be fairly well aged, I don’t think it’s necessary to issue spoiler alerts in each case. The comments all have spoilers.

Brian Daley’s Peripatetic Heroes

I first ran across Brian Daley (1947-1996) in his 1977 novel The Doomfarers of Coramonde, which has the irresistible premise that a sorcerer in a fantasy land summons magical assistance from another world—and it turns out to be an armored personnel carrier, with crew, from the war in Vietnam. The fish-out-of-water contrast was delightful and the action first-rate. I was primed to look for more good fun a few years later when Daley published Requiem for a Ruler of Worlds (1985), the first in a trilogy of adventures featuring the mismatched buddies Hobart Floyt and Alacrity Fitzhugh.

They’re still good fun. The heroes are both likable and relatable—dashing and mercurial Alacrity, a knockabout itinerant spacer with “friends in low places” across the starlanes, and staid Hobart, a minor bureaucrat from a congested backwater Earth. Alacrity has some personal issues to get over, mostly in the third volume, but Hobart develops most, rising to the occasion as he travels into space to obtain a bequest inexplicably left to him by an interstellar magnate. The worldbuilding is brilliant: planet after exotic planet, oddball character after still odder character. The sheer variety and colorfulness of Daley’s cosmos is pleasing.

The Floyt-Fitzhugh saga falls into the category of the “picaresque” tale. Originally I misunderstood that term to mean the same thing as simply “picturesque,” and the story certainly is that. When I actually looked up the word, many years ago, I realized it had a more specific meaning: “Characteristic of a genre of Spanish satiric novel dealing with the adventures of a roguish hero,” as Wiktionary puts it. That fits our heroes pretty well—Alacrity from the start, Hobart learning fast. They’re lovable rogues, often on the wrong side of the law (or at least local customs), with hearts of about 12-carat gold. Even in the last scene of the series, they’re off again to who knows where, one jump ahead of pursuit.

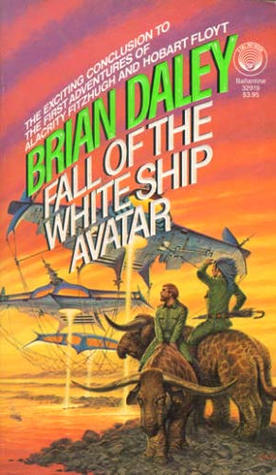

And thereby hang my possibly idiosyncratic reservations about the story. The plot of the first book is very good; there’s a clear goal and climax. In the second and third books, not quite so much. Alacrity and Hobart achieve some interesting results, but they themselves don’t actually stop to absorb or enjoy them. Our Heroes are always on to the next thing. Daley gives each of them a pretty good romance subplot, but these never quite resolve, since the MCs are always leaving their girlfriends behind—even at the end of the third book, Fall of the White Ship Avatar. I was left wondering, do these two ever get to settle down and enjoy the fruits of their labors?

This is a standard issue with wandering, picaresque heroes, particularly those who star in open-ended series. Daley even lampshades this aspect by including a whimsical journalist in the story who features Floyt and Fitzhugh in a series of utterly melodramatic “penny dreadfuls,” to Our Heroes’ perpetual embarrassment and annoyance. Daley seems to want to place them in the company of series heroes whose adventures never really end. James Bond is never going to stop secret-agenting; he just gets re-cast with increasingly younger actors. At the end of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, just when we might expect Indy to retire and be replaced by his son, Indy snatches back his rolling fedora at the last moment. The ending of The Incredibles or Spider-Man 2 show the characters resolving their personal character arcs, but nonetheless leaping into the next adventure.

One wonders if these perpetual adventurers ever retire, even as they inevitably age. We’ve pondered this previously in considering the “professional hero.” There has been the occasional hero who explicitly retires and passes on the mantle to a successor. There’s a neat little story in Kurt Busiek’s Astro City showing how superhero Jack-in-the-Box is training his successor. And Captain America eventually retires in the MCU, though the ‘line of succession’ is rather fraught.

Personally, I like to see the main characters settle down at some point, if only to enjoy a well-earned respite from perpetual danger and damage. They can continue to have interesting adventures later on; “happily ever after” need not be a static condition. Consider, for example, the somewhat atypical honeymoon of Miles and Ekaterin Vorkosigan in Diplomatic Immunity. But it’s satisfying to see beloved characters enjoying some degree of stability.

On the other hand, there’s also a certain appeal to the hero who’s eternally “out there,” a legendary figure, always at their peak and unabatedly themselves. In a way I don’t want to see Nero Wolfe or James Bond retire. So I do rather appreciate the perpetual motion of Floyt and Fitzhugh, despite the lack of resolution. To resolve, or not to resolve? That is the question—but either answer may be acceptable. I’ll be keeping the Daley books on my overstuffed shelves.

Stupid wordpress ate my comment. I’ll try again.

Never read any Daley, though I remember those covers from the bookstores, back in the day.

With picaresque and travel tales, as long as the characters end the book still on the road, then the conflict/problem that drives the story is in some sense not quite wrapped up. That might be why those don’t satisfy you. Get everything settled, and settle down, protagonists!

Finally, I’d love to hear your thoughts on Gentleman Jole sometime. Bujold is best, but there are a couple of things with that one where it doesn’t work for me.

Kevin Wade Johnson

LikeLike

I’m inclined to agree about Gentleman Jole. We will be ‘rereading’ that one shortly (as my wife and I go through the audiobooks, now on Cryoburn); at that point maybe I can pull together my reactions.

LikeLike