Science-fictional ideas have been gradually percolating through our popular storytelling and entertainment for years, as I noted at the beginning of these observations. One example is the idea of time dilation—that time passes more slowly at very high velocities—in the theory of relativity. The classic illustration is the “twin paradox.” We can trace this image from the science itself, through a classic novel, to—of all things—a rock song.

The Physicist’s Version

Those who are already familiar with relativistic time dilation can skip to the next heading. Otherwise, here’s a rough layman’s explanation of the phenomenon:

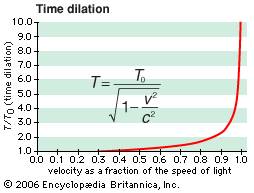

One of the consequences of Einstein’s theory of relativity, noted as early as 1911, is that time passes more slowly as we approach the speed of light. More precisely, a clock (or other process) that’s moving at a high velocity, relative to the observer, will be seen to operate more slowly than a clock in the observer’s own reference frame. If I sit in my comfortable lab on Earth and watch what’s happening on a spaceship accelerating away from the Earth, I’ll see the spaceship’s clock running slower and slower, falling further and further behind the clock on my wall. The closer to the speed of light (usually symbolized as “C”) the spaceship gets, the greater the discrepancy—the “time dilation.”

This isn’t an illusion. When the spaceship eventually returns to Earth, I’ll find that the traveling clock is behind the stay-at-home timepiece. The same is true for living organisms. If I planted a pair of trees before the ship left, the tree that made the flight may still be a sapling when it returns, dwarfed by its towering ‘sister’ on Earth. If you’d like the math, the Wikipedia article on the twin paradox gives an example for a trip to the nearest star, Alpha Centauri.

This isn’t an illusion. When the spaceship eventually returns to Earth, I’ll find that the traveling clock is behind the stay-at-home timepiece. The same is true for living organisms. If I planted a pair of trees before the ship left, the tree that made the flight may still be a sapling when it returns, dwarfed by its towering ‘sister’ on Earth. If you’d like the math, the Wikipedia article on the twin paradox gives an example for a trip to the nearest star, Alpha Centauri.

As with most of the peculiar consequences of relativity, we don’t notice such differences in ordinary life because they’re so small as to be undetectable at the speeds and scales we normally deal with. But if we look closely enough, the same effects are observable. Even the humble GPS app on your smartphone has to take into account the slowdown of the clocks on the GPS satellites, which move slowly compared to C but fast enough that the very precise positioning signals are affected.

Early on, physicists came up with a vivid illustration involving a pair of twins. If one twin takes a trip at near-lightspeed, she will end up younger than the twin who stays home.

At low velocities, the difference will be unnoticeable. A twin who spends a few months on the International Space Station will come back slightly younger than the stay-at-home twin, but only slightly. Up the velocity, though, and we up the ante. It would be quite startling, by normal standards, if the astronaut twin were still college-age while the earthbound twin were ready for retirement.

Sounds like a story, doesn’t it?

The Storyteller’s Version

Robert A. Heinlein’s 1956 young adult novel Time for the Stars does exactly this: it makes a story out of the twin paradox.

Tom and Pat Bartlett are teenagers growing up centuries from now. Tom is our viewpoint character. Pat is the “dominant” twin: he always seems to end up with the bigger piece of pie.

Tom and Pat Bartlett are teenagers growing up centuries from now. Tom is our viewpoint character. Pat is the “dominant” twin: he always seems to end up with the bigger piece of pie.

In this future, population pressure is extreme. The Long Range Foundation commissions twelve near-lightspeed “torchships” to look for colonizable planets among the nearby stars. The LRF has discovered that certain pairs of twins can communicate with each other instantaneously, by telepathy (which baffles the physicists no end, since that’s theoretically impossible). This gives the LRF a way for the starships to get their findings promptly back to Earth, and incidentally explains what an average teen is doing aboard an interstellar exploratory ship. One twin goes abroad; one stays home.

Heinlein’s characteristic mixture of sound scientific detail and relatable characters makes the novel a highly engaging story. We see the finagling by which it’s decided which twin (Tom) goes to space. We get a vivid picture of life aboard a starship that will travel independently for years (even according to its own time frame)—which is where I first learned the word “ecology.” We see strange worlds and watch how the people aboard the Lewis and Clark (known to its passengers as the “Elsie”) interact.

Time dilation is described with realistic detail. As the Elsie approaches the speed of light (never quite reaching it), Tom has to “speak” to his brother more and more quickly, and Pat on Earth has to communicate more and more slowly, because their time frames are increasingly out of sync: “he complained that I was drawling, while it seemed to me that he was starting to jabber” (ch. 11, p. 113).

But it’s the age difference that makes things really difficult. At the end of the first near-lightspeed jump, Pat is eleven years older than Tom and has a seven-year-old daughter, Molly. It becomes harder for Tom and Pat to connect; they’ve grown apart to the extent that they now have little in common. Fortunately, it turns out that the twins’ connectedness can sometimes be passed on (stretching the original concept considerably): Tom can communicate with Molly as well. As time goes on, Tom’s connection with Earth is increasingly through his brother’s descendants, though Pat is still alive.

The Lewis and Clark’s expedition ends when she’s met by a new ship from Earth. Based on investigations into the instantaneous telepathy, scientists have developed a new theory that allows for an “irrelevant” space drive—one that can whisk the whole crew home in mere hours. The twin imagery is vivid when college-age Tom meets his brother Pat, now an old man in a wheelchair. The time slippage is even more pointedly illustrated when Tom meets his great-grandniece Vicky, whom he’s spoken with telepathically for all of her life—and is now going to marry. (The appearance of incest is illusory: Tom and Vicky have only 1/8 of their parentage in common, or five degrees of consanguinity in terms of Wikipedia’s table.)

Jo Walton has a review with a fascinating (and telling) aside on what Heinlein’s book would have been like if it were written today, rather than in the 1950s. But we’re going to go on to look at a more unlikely treatment of time dilation.

The Musical Version

As far as I know, no one is contemplating making Time for the Stars into a musical. But years ago I ran across a song on a 1975 album by the rock band Queen. The song is called “’39.” The official lyric video gives you both the recording and Brian May’s lyrics. Note the imagery the band chose for the introductory graphics.

If you didn’t have the lead-in we’ve walked through here, the song might seem rather baffling. The acoustic sound, the rather antique style, and the mention of sailing off to discover new lands makes us think of olden times. But what’s with “. . . the day I’ll take your hand / In the land that our grandchildren knew”?

If you didn’t have the lead-in we’ve walked through here, the song might seem rather baffling. The acoustic sound, the rather antique style, and the mention of sailing off to discover new lands makes us think of olden times. But what’s with “. . . the day I’ll take your hand / In the land that our grandchildren knew”?

One clue is the songwriter’s coyness about the first two digits of the date that forms the title. If someone says “’39,” we normally assume they mean 1939. But there was nothing like this happening in 1939. The song is full of this careful ambiguity.

If you come to the song with a science-fiction background, however, it’s clear what it’s really about. Clues are scattered all through the lyrics. We’ve got the population pressure: “the days when lands were few.” The brave crew is “inside” the ship, rather than “aboard.” It sails “across the milky seas”—the Milky Way. The singer is “many years away” from his beloved. The Volunteers bring back news of “a world so newly born” to colonize. Most significant, he’s “older but a year,” yet the earth and his beloved have radically changed. We haven’t got twins or telepathy in sight, but otherwise, we might well be talking about the mission of the Lewis and Clark.

When the Web was invented and I finally looked up the song in Wikipedia, I was tickled to find my guess was correct. According to the Songfacts site, the composer May studied astrophysics, and he himself has referred to the piece as a “sci-fi folk song” (commonly referred to as a “filk song”).

The story line isn’t as clear as Heinlein’s, to be sure. For one thing, the traveler seems astonished at the relativistic time slippage when he returns (“this cannot be”). No real astronaut would be that unaware of what to expect. In addition, in the chorus the singer seems to be addressing both a stay-at-home spouse with whom he’s had grandchildren (“my love”), and a descendant (“your mother’s eyes”)—unless perhaps, like Tom Bartlett, he’s fallen in love with a much younger family member.

In any case, with the necessary compression of a story into the poetry of lyrics, we don’t expect as literal a narrative as in a novel—particularly when, as here, May seems to have been deliberately indirect, even tongue-in-cheek, as a sort of joke on the listener.

But, just as in the novel, the song’s emotional resonance involves a romance as the most poignant expression of the results of time dilation. It also ends with an appeal for sympathy with the personal dislocation of the narrator, who returns to a world far different from the one he left (“For my life still ahead, pity me”)—a theme also touched on at the end of Time for the Stars.

The three-part comparison reminds us that, even as far back as the 1970s, science fiction turns up in the darnedest places; and that scientific developments can bring new aspects to the timeless concerns of our hearts.

Another well written and insightful blog! As to the content…yes, for a Sci Fi writer, Einstein’s “speed limit” can be a pain in the backside. 😦

LikeLike

True. But it also gives rise to a lot of interesting stories. As usual, my plan is to have my cake and also consume it: have a historical period where all star travel was slower than light, then introduce FTL travel and explore *those* possibilities. 🙂

LikeLike

Ooo, so many things to put thought pennies on 🙂

I can’t resist and nurd a bit (though a big disclaimer: relativity is not my expertise), and nitpick about some of the theoretical/scientific details.

— I’d be surprised if time dilation became widely known as a consequence of relativity only in 1911. It’s there in the equations, and the equations themselves, funnily enough, are due to Lorenz, not Einstein. By 1904 or 1905 at the latest, both Lorenz and Poincare had published something to the effect of, hey look, time changes too under these equations. (The story of how Special Relativity came to be is rather weird, unless one remembers Newton’s comments about giants’ shoulders, and Einstein’s quip that a genius hides his sources)

— There’s two kinds of relativity, and while one kind (the Special) was definitely in the air by the time Einstein connected the final dots, the General is certainly more his own (and Minkowski’s). Both also, happily enough, provide kinds of time dilation: speed-based for Special, gravity-based for the General. I don’t know exactly which effect dominates in the case of GPS satellites, but I’ve heard it said that the timing difference one needs to account to is one of the proofs of General Relativity. Time flies slower, so to speak, in a gravity well. A clock on Earth is slower than one in space, also because the one on Earth is closer to a big mass.

— The twin paradox came to be because the consequences of relativity were/are very hard to stomach. Any number of such paradoxes were put forth, in an attempt to prove that the theory was inconsistent, therefore its unintuitiveness could then be explained away and ignored as some feverish fancy. This is how the twin paradox started: you have a ship, and the Earth, with a twin on each. The ship flies away at near lightspeed (from the Earth twin’s perspective). However, all is relative, which is another way of saying everything is symmetric: according to the ship’s twin, it’s the Earth that flies away at near lightspeed. So each twin sees the other as moving, with a slower clock, and aging slower. Conspire to bring the twins back together again (maybe the ship takes a big arc), and each twin sees the other as aging slower, even when the ship and Earth approach so you should get “the latest” data. But it cannot be that both twins see the other as younger. One must be younger, but then again a problem: the situation was symmetric, so if you can tell which twin is younger you can tell who moved, breaking relativity.

Obviously there’s something wrong with that interpretation 😉 The simplest flaw one can point in the allegedly paradoxical scenario I described above is that it involves acceleration (the ship must accelerate to lightspeed, decelerate and turn back etc.) which brings it out of the domain of Special Relativity. But actually even if we allow instantaneous switches between inertial frames (one ship flies out from Earth, one ship flies toward Earth and when the ships meet the Earth-bound one takes the clock value of the other), the effect is present: a clock on Earth would have aged more than the number of ticks the Earthbound ship has counted (including the ticks it took from the out-bound ship). It is the switching itself of the inertial frames that causes the difference in clock values.

Oh, and I heard Heinlein was very open about close family members getting, shall we say, closer. The horizontal tango with a great-great-grandniece is peanuts, but I get this from second hand sources. The only book of his I’ve read (very, very long ago) is Double Star. I remember it as being rather interesting, and it made me appreciate what gs are.

Cheers.

LikeLike

lol . . . The ideal post is one where the replies are longer than the post itself. 😉

Before 1911, yes. I spoke loosely: it was actually in 1911 that the “twin paradox” was proposed, or so I’ve read. (After all, it’s the “Lorenz-Fitzgerald contraction,” not the “Einstein contraction.”

I didn’t want to get into gravitational time dilation, since my focus was on space trips. Similarly, I skated carefully around the early debate about which twin aged faster. I always understood the “paradox” in the name as being simply the fact that they aged at different rates, rather than the asymmetrical-reference-frame business. I’m not a physicist either, I just like to dabble . . .

Yes, Heinlein wouldn’t have been bothered at all about the relationship between Tom and his great-grandniece. I can recommend quite a lot of his stories, especially the juveniles — but some are decidedly NSFW.

LikeLike

I should put some Heinlein on my to-read list actually. He’s definitely a different style than the other two greats of the classic SF age.

He’s written so much that it’s hard to know where to begin, or what to look for, lol. I suspect he did things which don’t always fall into the usual adventure plot skeleton (though I don’t mind those, and I’ll probably just start with a simple honest adventure).

Cheers!

LikeLike

Aha! Even an implied query about what to read is likely to trigger suggestions. 🙂

Heinlein’s juveniles may actually be his best work — though I wouldn’t read too many consecutively, or the similarities in characters and tone may make them tend to run together. They’re all good; I particularly recommend Have Spacesuit, Will Travel, The Rolling Stones, Between Planets, Citizen of the Galaxy, Farmer in the Sky, Red Planet, Space Cadet, Starman Jones, Time for the Stars, and Tunnel in the Sky.

Next, I’d look to some older novels: Double Star, The Door Into Summer, The Puppet Masters. But his best single novel may be The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress.

The Future History stories vary in quality, but they’re worth reading not only for their own sakes, but as an illustration of how a future history is built. There’s a one-volume version (The Past Through Tomorrow); the original separate volumes are The Man Who Sold the Moon, The Green Hills of Earth, Revolt in 2100, Methuselah’s Children, and Orphans of the Sky. All but Methuselah are actually made up of short stories or novellas.

There are some ‘milestone’ books that are classics of the field, though opinions may vary as to individual quality. Here I’d group Stranger in a Strange Land, Starship Troopers (ignore the movie, please), Glory Road.

There are a number of short stories that are classics in the own right, including two iconic time paradox stories, “By His Bootstraps” and “All You Zombies.”

In the later stuff, things get complicated. Most of them are readable, but the quality varies (sometimes within the same story). Some of them purport to be continuations of the Future History — most notably Time Enough for Love — or possibly of all his fiction, weird as that sounds. (See The Number of the Beast.)

Oh, well, I get carried away. This reply is practically long enough to be a blog post in itself. Hmm . . .

LikeLike

Ah, “esprit d’escalier” moment. On the twin paradox–

Ideas are created (or found, depending on how one prefers to think of this), then move in other domains. But in doing so, they change. The twin paradox started as a somewhat dry thought experiment about a strange implication of relativity. But that is no longer what is known as the twin paradox. It moved into art, and there it is not enough to be logically weird, one should also be emotionally poignant, and the salient “paradoxical” feature was no longer the alleged inconsistency, but the gap in time and development that is inserted between beings who should ‘naturally’ move through the world together.

Cheers.

LikeLike

Exactly!

“esprit d’escalier” — cool — I hadn’t heard that one before.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Stroke of Lightning | Rick Ellrod's Locus